Etching falls under the intaglio and engraving category of printmaking, where the printing press applies great force to push ink into lines. Though an etching is an engraving, not all engravings are etchings. The key difference between the two comes down to the use of ground and acid. Where an engraving results from just the artist???s efforts with various tools and a metal plate, an etching requires acid baths to ???carve??? out an artist???s lines.

Etched illustrations started to be used in book printing in the 16th century. Unlike the more labor-intensive process of engraving, etching allows artists to sketch freely on a copper plate that has been prepared with a wax coating called ???ground.??? The artist uses a sharp tool to draw into the wax, revealing the bare, unprotected copper below. Upon completion of the illustration, the plate is dipped into acid. The acid ???bites??? through the artist???s lines. Any portion of the plate with wax intact remains protected. After removing the leftover wax on the surface, the copper plate etching resembles an engraved plate and can undergo the same printing process.

Etching allows for ease in creating depth. The artist will ???stop out??? a plate by removing it from the acid and drying it. Once dry, the artist varnishes lines intended to appear shallower to protect them from subsequent dips. Later dips bite deeper into the unprotected lines, creating deeper, darker lines in the print. Artists also may illustrate in stages, drawing in the darkest tones first and then adding mid and light as they progress through subsequent acid dips.

Artist Edward Borein provides an interesting example of this variation in depth. The above etching suited Borein???s preferred style of pen-and-ink illustration. The darker tones of the mule and the shadows of the men indicate that these portions underwent more acid dips to deepen the lines.

On first glance, etchings and engravings might appear indistinguishable. In fact, many plates contain both techniques combined, further complicating identification. Common hallmarks of etching include spidery line works (more akin to a ballpoint pen sketch in appearance than the graceful swells of engraved lines); free flowing marks as opposed to tightly grouped patterns; blunt starting and stopping points of strokes; and loose shape suggestions.

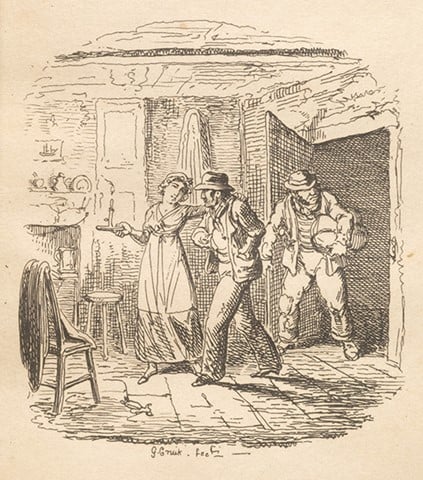

Movement defines Cruikshank???s etchings as evidenced by the fluid use of lines here. The dish and pitcher melt into the mantle. Though they lack grounding points, they remain recognizable. The crosshatching near the bottom right has broken lines, uneven spacing of the negative areas, and blunt strokes without tapered ends. Each line appears spontaneous rather than the deliberate repetitious strokes apparent in engravings.

Subject matter also helped to determine which technique an artist employed. Engraving best suits static subjects: portraits, maps, text within illustrations, architectural elements, and symbolic pieces such as wreaths, urns, and banners, whereas etched illustrations often evoke movement and spirit, preserving a moment in time. Bustling city scenes, comedic events, emotional interactions, and nature scenes abound among etched illustrations. However, skilled artists could use either technique to great success regardless of their subject.

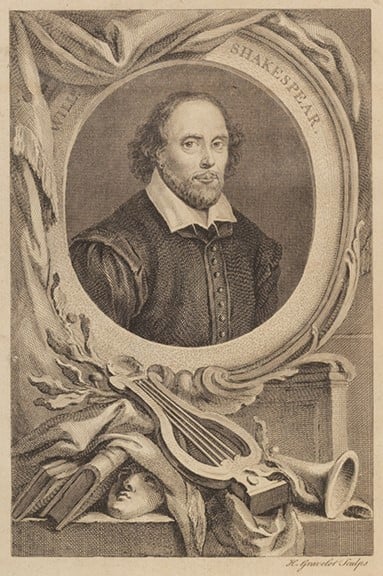

This plate displays several key elements that make it easily identifiable as an engraving???subject matter consisting of symbolic stationary objects, text within the illustration, and a central portrait.

Magnified, the line work displays further indicators of engraving as opposed to etching. Notice the clean and smooth swooping arches used to shade and shape the cheek of the mask. These evenly spaced and carefully grouped strokes also taper at the end.

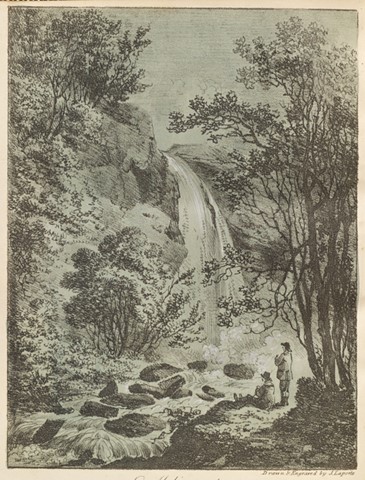

The artist of The Scenery, Antiquities, and Biography of South Wales, J. Laporte, sketched each illustration in real time. Etching the illustrations then enabled Laporte to convey the rushing water and its downward flow, capturing a specific and fleeting moment. Nature is an ideal subject matter for the medium.

When etching and engraving are both used in an illustration, etching usually serves to fill in backgrounds, whereas engraving is usually used for the central subject or text. Even within the same subject, though, a magnifying glass may reveal both methods intertwined to create a cohesive element. Since these two illustrative processes often share the same space, and an etching falls into the engraving category, collectors and dealers usually label them simply as engravings. This categorization, while appropriate, can also cause confusion.

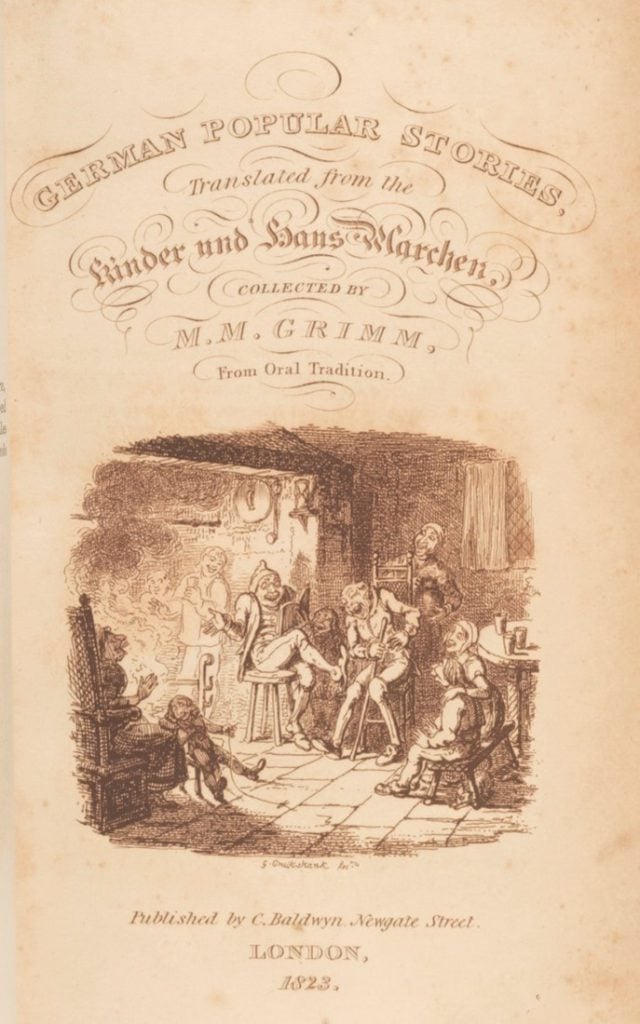

Cruikshank provided etchings for the first edition in English of Grimm???s Fairy Tales, 1823, 1826. Frontispiece illustrations that appeared alongside title pages, or served as the title page on their own, often contained a combination of engraving and etching. Here, this frontispiece primarily consists of etching with engraved text.

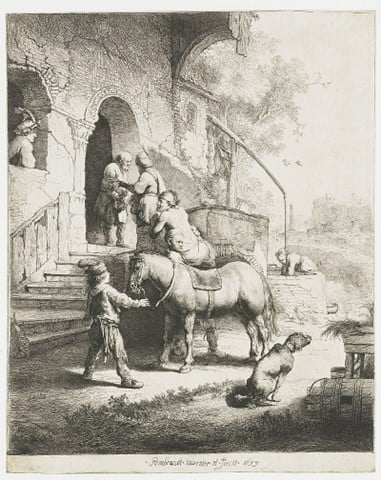

Fine artists produced some of the greatest etched works???Goya, Degas, Manet, Picasso, and Dali among them. While many artists dabbled in the method, Rembrandt remains the master of the medium as its most revered and most innovative practitioner. He experimented with every facet of etching, from ground recipes and acid strength to how to wipe the plate and the type of paper to print on. His etchings proved popular among collectors during his lifetime. The ability to mass-produce etchings and the lucrative nature of those etchings offered Rembrandt the freedom to create. He would sometimes spend years working on a single plate.

Rembrandt???s constant tinkering with plates makes his etched prints particularly fascinating. During the etching process, he would produce prints from the same plate at different stages. A single Rembrandt etching might result in numerous prints with subtle variations. These are called ???states.??? Though not unique, etched prints by fine artists remain highly collectible artworks. While they are generally less rare and more affordable than drawings or paintings, some prints are sufficiently scarce to demand notably high prices.

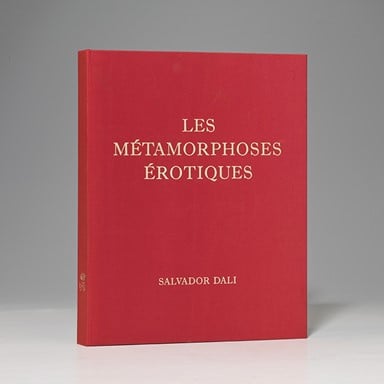

While artists occasionally released works as standalone prints, they also created collections of etchings on loose signatures (pages without a binding to gather them together) printed on luxurious paper and then laid into portfolios. These works might accompany a related text, but might also comprise a self-contained art suite. The lack of traditional binding can be an advantage: it makes it easy to handle or display individual etchings and elevates the overall presentation and extravagance of the work.

Dali created several illustration suites, such as the one above, in which his art appeared as a loose collection of plates held together in a portfolio. This title includes an original etching signed by Dali.

For more examples of great etched works, you may want to visit our website for items such as:

#115130 Pablo Picasso???s Corps Perdu

#124704 Matisse’s version of Joyce’s Ulysses