Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.

In 1955, one of the most beautiful and controversial works in English would be published. Called ???repulsive,??? ???disgusting,??? ???revolting,??? and ???corrupt,??? the book was written by a professor at Cornell who taught a class on Masterpieces of European Fiction.

The professor, Vladimir Nabokov, had published a few books previously in America, but all were financial failures. Fearful that the publication of Lolita would get him fired from his Cornell position, Nabokov first sent the manuscript out secretly to friends in American publishing, calling it his ???time bomb.???

One publisher after another rejected the manuscript. The Viking Press explained, ???we would all go to jail if the thing were published.??? Another publisher claimed:

[We] feel that it is literature of the highest order and that it ought to be published but we are both worried about possible repercussions both for the publisher and the author.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of these rejections was the approval of the editors who read the manuscript. Although reactions were mixed, many of these initial readers recognized Lolita???s literary value. One editor, Jason Epstein, even resigned from Doubleday largely on account of the company???s refusal to publish the novel.

But this was an era when censorship and the qualifications for obscenity in literature were still being defined. According to Edward de Grazia*, ???Not until June 1959 did the Supreme Court make it clear that a work could not be banned for its sexual immorality.??? Also noteworthy is the context of McCarthyism during these years, which brought on a slew of prosecutions of publishers and writers.

Nabokov was well aware of these difficulties. In his early correspondence he insisted the work be published under a pseudonym, and even worried about sending the manuscript to publishers in the mail, afraid the US Postal Service would catch it in an inspection before it was even published.

The solution? Send one of the best books written in English to be published in France.

Two years earlier a small publishing house called the Olympia Press had been formed. Nabokov had been referred to its owner Maurice Girodias, who was thrilled to take on the project.

The Olympia Press had quickly gained a reputation for publishing dirty books, so-called ???dbs,??? but often with somewhat ???literary??? content. Girodias took pride in his extremely clever business model: he hired many literary writers who were struggling for money to churn out essentially pornographic works, which put food on their tables while they slaved away on their real masterpieces.

Nabokov was actually unaware of the reputation of this new press, which he discovered only later and with much dismay. He wanted Lolita to succeed on its literary merits, not become a bestseller because of scandal:

Lolita is a serious book with a serious purpose. I hope the public will accept it as such.

That said, Nabokov was becoming desperate. Looking back he wondered if he would have made the deal with Girondias had he known the publisher???s reputation. ???Alas, I probably would, though less cheerfully.???

In all fairness, Girondias really did have an eye for excellent work that others called ???obscene??? and ???unpublishable.??? He was also the first publisher of some works by Henry Miller, a number of Samuel Beckett???s English works, William Burroughs???s Naked Lunch and J.P. Donleavy???s The Ginger Man. Said Girondias of Lolita:

I sensed that Lolita would become the one great modern work of art to demonstrate once and for all the futility of moral censorship???

Before the book was published in Paris in 1955, Nabokov eventually did come around to putting his name on the cover. Unsurprisingly, a number of friends and associates have since stepped forward to claim they had nudged him into the idea. Regardless, Nabokov seemed ready to take the risk with Cornell. According to his son Dmitri, ???And of course, once the book was out, Cornell became proud of Lolita.???

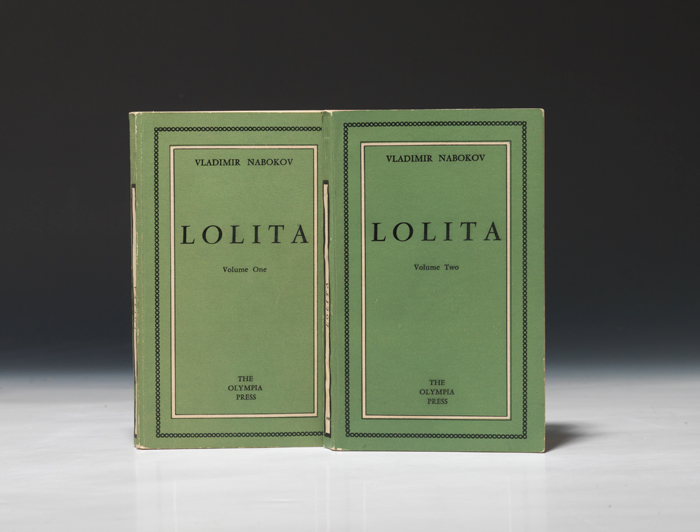

The publication in 5000 copies by the Olympia Press, in its characteristic green wrappers, sold out quite quickly. In fact, the bibliographic point to determine the first issue of the book is the price of ???Francs: 900??? on the back wrapper. Brisk sales convinced Girondias early on to raise the price to 1200 francs, which he changed with a sticker on the wrapper. It is one of the few masterpieces of the 20th century that was first published in a ???softcover??? format.

Lolita was viewed as comical to some, tragic to some, and obscene to others. Nabokov naturally disagreed with this last category of readers, explaining that ???Lolita is a tragedy???the tragic and the obscene exclude one another.??? A contemporary review from the New York Times captures the dual nature of this book that changed modern literature:

The first time I read Lolita [in an abridged format] I thought it was one of the funniest books I???d ever come on???The second time I read it, uncut, I thought it was one of the saddest.

*I am indebted to Edward de Grazia’s book Girls Lean Back Everywhere for a large portion of the source material used in this post. If this story and the history of 20th century literary censorship interest you, I highly recommend this work.

Comments

7 Responses to “The Story Behind Lolita By Vladimir Nabokov”

cheyenne says: September 30, 2013 at 9:11 pm

The movie was ideally cast with James Mason .

Christopher Denny says: July 11, 2014 at 2:28 am

A few random comments on Lolita: It was first book Nabokov wrote in English. Imagine that ! With Ulysses, it generally tops best books of the 20th Century lists….It’s important to remember that Humbert sees in Lolita his lost childhood love. This, of course, doesn’t excuse his behavior, but it helps to explain it. Was her death the source of his psychological imbalance?…A lot of that part of the story in the opening pages is evocative of Poe–quite intentionally. (For a deeper appreciation of this masterpiece, The Annotated Lolita is essential reading.)…There’s also a couple of recordings available: One of James Mason reading selections from the first part of the book and another with Nabokov reading mostly from the second part of the book; particularly Humbert’s confrontation with Quilty…Two other interesting reads for fans of the book are Nabokov’s screenplay for Lolita (which Kubrick never used, but is in print) and Nabokov’s prototype for Lolita: a novella called The Enchanter (his last work in Russian). It wasn’t published in his lifetime…After reading and experiencing all of the above, there were still several things I’d never heard or read before in Rebecca’s post. Thanks, again ! PS I haven’t seen the show yet, but I’m looking forward to it.

Rebecca Romney says: August 15, 2014 at 10:43 pm

Thank you for the additional sources readers can explore!

Personally, I find that many people who take issue with the basic plot summary of the Lolita haven’t actually read the book. As you say, there’s a lot more going on.

Christopher Denny says: August 20, 2014 at 9:21 pm

I wanted to congratulate you, Rebecca, on your forthcoming blessed event. I wish you & your family ever happiness.

Jerry Yanoff says: October 4, 2014 at 1:54 am

Being 75 I have grown up with the changing rules in censorship. As a teen ager in the 50’s we would joke about copies of Ulysses. In my early 20’s I read Lolita which really was a beautiful book in that it looked into the soul of a disturbed man. The writing was beautiful as you have shown by printing the opening passage. The movie was rare in that it was so well cast. The one concession was that Lolita was 16 where in the book she is 14. James Mason, Shelly Winters and Peter Sellars were all brilliant.

Rebecca; Thank you for bringing up this discussion. I do hope that someone who does not like this book will print his or her comments.

Susan says: August 14, 2018 at 1:20 am

Lolita is anything you crave and shouldn’t touch. It’s a boy, it’s a girl, and that raw carnal energy of sexual awareness. The innocence and the power are a sexual taboo. And the sweet spoiled sadness of its outcome always makes me cry.

Joseph Sechler says: November 15, 2018 at 10:54 pm

After seeing Lolita near the top of literary “great novel lists” for years I listened to Jeremy Iron’s narrated audiobook version. I knew the basic premise of the novel in advance, and that had not made me want to read it. However, once I started it I was, and remain, hooked on Nabokov’s ability to shape the English language into art. I did become intrigued with why he did write Lolita. Of note, the story goes (not sure if true) that he wanted to burn the manuscript, and more than once his wife talked him out of it. That implies he found the subject disturbing and or painful, but that she felt he needed to finish the act of writing it. I read his excellent autobiography, Speak Memory, for enjoyment but also with an eye for clues in his life that may have led to writing Lolita. I believe the clues are there, though he does not dwell on them.