The French folktale of a murderous nobleman called Bluebeard had been around for the better part of two centuries by the time Charles Perrault published his version in Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passe in 1697.

There???s some debate, but most agree that the tale is based ??? at least in part ??? on Baron Gilles de Rais, a 15th-century Breton knight.* Publicly, he was a wealthy war hero, who served alongside Joan of Arc in the French army during the Hundred Years??? War. Privately, he was a prolific abuser and murderer of children. Even among stories of the depraved, this guy stands out.

It makes a kind of sense then that such evil would become the basis for a fairytale boogieman.

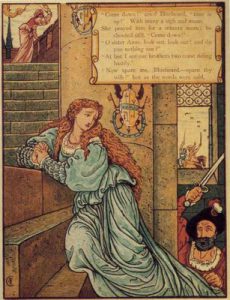

The tale, in case you???re not already familiar, involves a wealthy man called Bluebeard, his reluctant young wife, and a locked room that he forbids her from entering. Unable to stave off her curiosity, the young wife waits until her husband is away and then opens the room. She discovers the dead bodies of Bluebeard???s previous wives.

When he learns that his wife has opened the room, Bluebeard flies into a rage and attempts to behead her. The wife delays her execution with some Scheherazade-style ???final prayers,??? and at the last minute, her brothers burst through the door and dispatch Bluebeard posthaste.

Like most fairytales, the story has proved a rich source of inspiration. The (implied) dangers of marriage, curiosity, greed, and women in general have been spun and re-spun by myriad writers and artists: Charles Dickens, William Thackeray, Anatole France, Walter Crane, Gustave Dore, Harry Clarke, Kurt Vonnegut, Angela Carter, Margaret Atwood, Francesca Lia Block, and even the DC Comics series Fables.

Because the tale can so easily be read as a matter of masculine authority versus a (seeming) lack of feminine agency, many of the retellings ??? especially in the 20th century ??? revolve around the idea of power. Who???s got it and/or who???s taking it? In these versions, a woman is usually the savior ??? the wife herself, a mother, a sister. Among my favorite of these retellings is Angela Carter???s ridiculously well-written short story, ???The Bloody Chamber.???

For me, the most compelling reimagining of Bluebeard, however, comes in the form of a sonnet written by Edna St. Vincent Millay. (Originally published as ???Sonnet VI??? in 1917???s Renascence and Other Poems, the poem is now most often listed simply as ???Bluebeard.???)

This door you might not open, and you did;

So enter now, and see for what slight thing

You are betrayed??? Here is no treasure hid,

No cauldron, no clear crystal mirroring

The sought-for Truth, no heads of women slain

For greed like yours, no writhings of distress;

But only what you see??? Look yet again:

An empty room, cobwebbed and comfortless.

Yet this alone out of my life I kept

Unto myself, lest any know me quite;

And you did so profane me when you crept

Unto the threshold of this room tonight

That I must never more behold your face.

This now is yours. I seek another place.

If ever you were looking for an example of literature and art???s power to transform, here it is. In a mere 14 lines, Millay manages not only to make Bluebeard a sympathetic character, but she also undoes (if only temporarily) more than five centuries of villainy.

What about you? Any favorite retellings of classic tales?

*Many scholars also cite Conomor the Accursed, a 6th-century Breton king known for his cruelty, as an inspiration for the tale of Bluebeard. Conomor was in the habit of beheading his wives when they became pregnant.

Comments

2 Responses to “I Seek Another Place: Edna St. Vincent Millay???s ???Bluebeard???”

Margot K Juby says: February 1, 2014 at 12:12 pm

The story of Bluebeard certainly was not based on Gilles de Rais. I doubt whether it was even based on Conomor, though, as a wife-killer, he has by far the better claim. There are so many similar tales, from all over the world, going right back into history; I think Perrault was drawing on a much older tradition.

The confusion between Gilles de Rais and Bluebeard goes back to the Abb?? Bossard, who wrote the first proper biography of the former. He wrote it originally as a thesis, and chose to try and establish a GdR/Bluebeard connection that had never existed before that time. He cited three “traditional” stories to back up his point – interestingly, although his book is lavishly footnoted and he cites the exact page of every text quoted, at this point he becomes lax and none of these stories is given an adequate provenance. In fact, where he does try to source a Breton lament to a writer called d’Am??zueil, a later biographer of de Rais drily commented that he had been unable to find this particular poem anywhere in d’Am??zueil’s published works. The suspicion is that all these traditional tales are forgeries, possibly created by Bossard himself to prop up his thesis.

In fact, for 350 years after his death, until his tomb and memorial were swept away in the Revolution, Gilles de Rais seems to have been seen as a quasi saint. The Bluebeard tradition that is undoubtedly associated with his name now is entirely attributable to Bossard. In 1992 he was retried and found not guilty, a likely victim of political and financial plotting under the aegis of the Inquisition – but that is another story…

Embry Clark says: February 10, 2014 at 6:46 pm

Hi there Margot, many thanks for these additional details! As you say, it’s often nearly impossible to track fairy tales back to a single source, especially given that the literary traditions of so many cultures share similar narratives. While a number of scholars have cited Gilles de Rais as part of the tale’s inspiration, there is certainly much debate, as you point out.