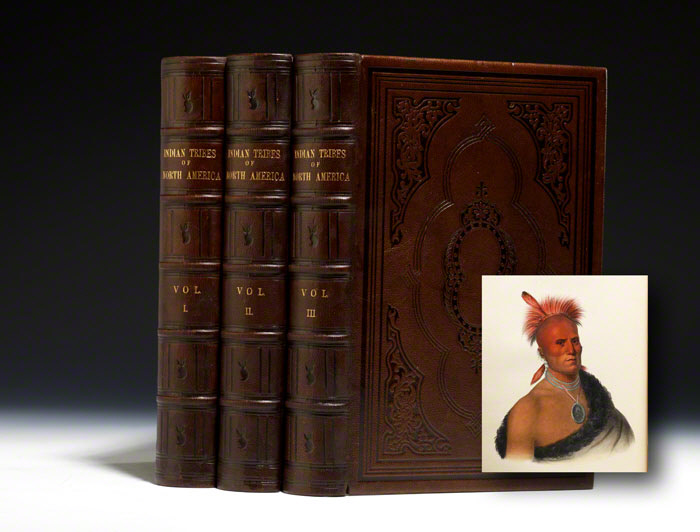

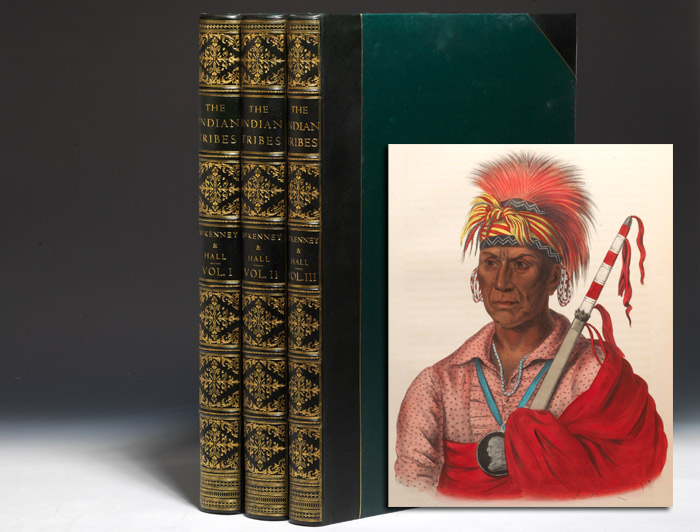

Thomas McKenney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs under presidents Madison, Monroe, Adams, and Jackson, sought to create an archive that would preserve the American Indian heritage and traditions of the time. With 120 stunning hand-colored lithographic plates, the result was one of the most beautiful and historically significant publications in American history ??? though its success certainly didn???t come without many difficulties. Here is our run-down of the publication.

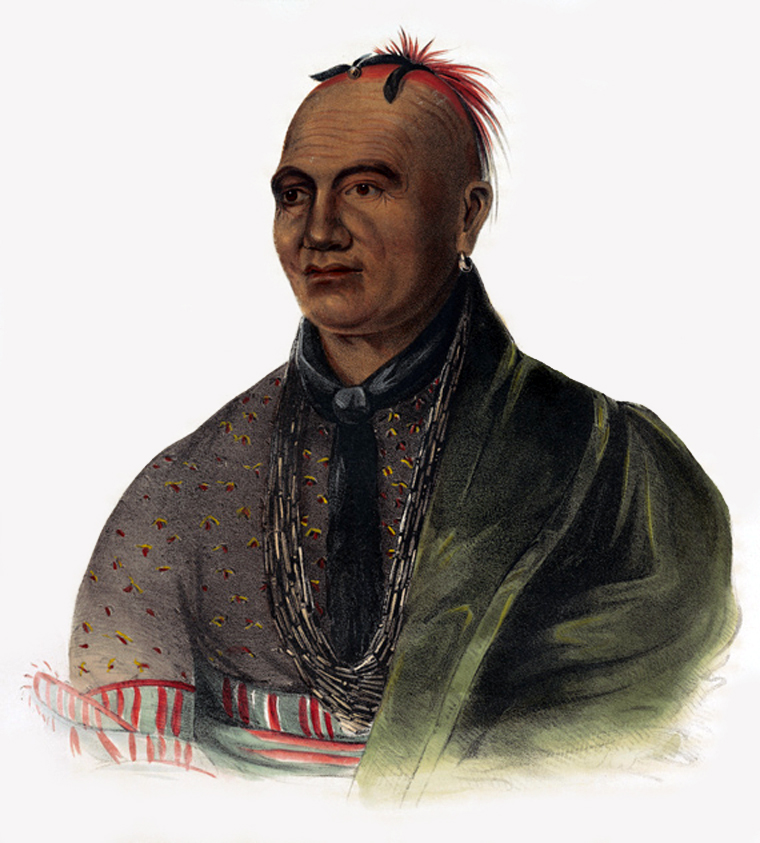

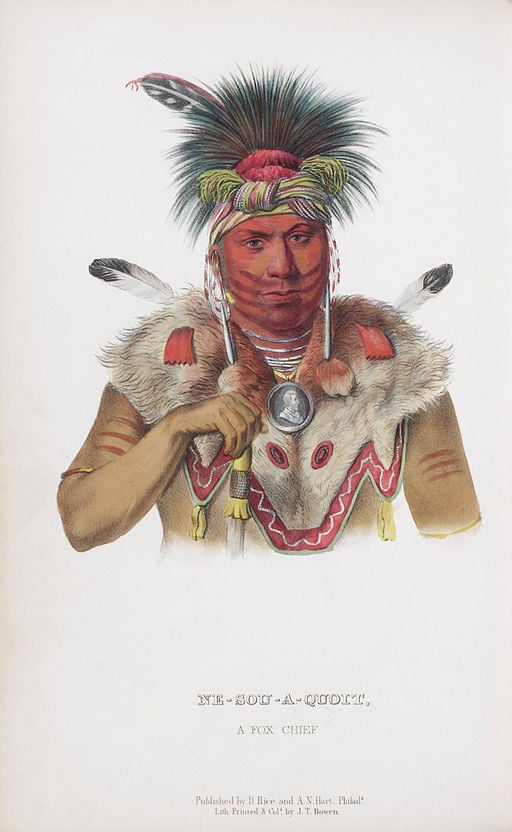

1) In 1821, Thomas McKenney commissioned painter Charles Bird King to paint portraits of the Indian dignitaries that visited his office in Washington. This assignment would last until 1842, and by the end, King would create more than 143 paintings.

2) Following an order from his superiors to cease production because of the mounting cost of the project, McKenney decided to publish the work in book form, and in 1829 partnered with printer Samuel F. Bradford from Philadelphia. Bradford quit the project four years later, due to financial struggles. During these four years, he created only 12 lithographs and gained only 104 subscribers.

3) Printers Edward C. Biddle and John Key agreed to take on the project with the firm Childs and Inman, completing additional paintings and lithographs. However, their business collapsed two years later, despite the collaboration of landscape artist George Lehman and a change in management.

4) Good fortune returned in 1836, when James Hall agreed to write for McKenney. Hall spent eight years gathering information from human sources. Childs and Lehman also returned to complete the lithography.

5) The first prints of the project were published in 1837. They were met with high praise and gained 1,250 patrons and an income of $150,000. King was then commissioned to paint more portraits. Up to this point, no fewer than four combinations of partners had worked on the lithographs, and the first volume of 48 plates was a mix by several firms and publishers.

6) The depression that followed the panic of 1837 hit the core group of subscribers. Philadelphia printers Rice and Clark became the fifth and final publishers of the project.

7) At this point, McKenney goes his own way, but the publishers push the project to completion; The last volume in the edition limps into view in 1844, putting the final number of plates at 120, some 14 years after the project began.

8) A number of King???s original paintings were damaged in the Smithsonian fire of 1865, making the book and lithographic printings even more valuable.

9) The creation of the History of the Indian Tribes persuaded John James Audubon to release an octavo version of his famous lithographic work Birds of America.

10) Today the work stands as one of the most important historical documents of Native American history.

Comments

7 Responses to “Indian Tribes of North America by Thomas McKenney and James Hall”

luca giannelli says: February 10, 2014 at 4:03 am

i note some differences with piola’s one… and the role of james otto lewis, partner, ennemy or both? regards

Sean Samuels says: May 27, 2014 at 8:23 pm

Hi, Luca, thanks for your comment. Here’s a little something to consider regarding James Otto Lewis, which Rebecca has been researching of late.

Before the bankruptcy of 1839, for various reasons seven years expired between McKenney???s first view of proofs and the publication of the first part of the work in 1837. This opened a very small window for Lewis, who did everything he could to pry that window into a major doorway. While most of the portraits from McKenney???s Indian Gallery had been painted by Charles Bird King in Washington, Lewis had also been occasionally commissioned by the government to produce paintings on Native American subjects. Now McKenney was using some of his paintings for a private work that everyone believed would result in significant financial gain for the former Superintendent. Lewis received nothing beyond the original commission fee for his work. So while McKenney???s project languished, Lewis sprang into action to create a large format Native American color plate book of his own, as an early advertisement says with a lovely little undertone of malice, ???the first attempt of the kind in this country.???

Lewis???s Aboriginal Port Folio, comprised of 80 hand-colored plates, was the largest color plate project published in America before McKenney???s publication. [11] The entire production was priced at $20 for subscribers, as compared to McKenney???s $120. ($500/$3000) Lewis rushed into publication between May of 1835 and January of 1836, essentially publishing one fascicle of ten plates every month???a pace entirely unheard of among American publishers at the time. He was right to do so. Lewis had planned to publish all ten parts before his competition could compete in the market, but he didn???t quite make it. And when McKenney???s project finally came to fruition, it blew Lewis???s project away.

In this century many productions sold by subscription struggled to reach completion because subscribers delayed payment or stopped subscribing altogether over the years. There are only about half a dozen sets of Lewis???s Aboriginal Port Folio that survive complete with all ten parts, as opposed to dozens of sets missing just the last set or the last two. Historians have attributed this, I think correctly, to the superior McKenney project luring both lithographers and subscribers away.

Amanda DeGidio says: July 30, 2019 at 11:19 am

I’ve been searching and searching for a simple rundown of the history of these prints. This is so fantastic- THANK YOU!!!

Michael Aakhus says: December 31, 2019 at 9:04 am

I have three hand colored lithographs from the Indian Tribes of North America, McKenny and Hall. I plan to donate the prints to the Art Collection of the University of Southern Indiana and require and appraisal. I was hoping that you might be able to provide that service. I can forward images that include: Shing Gaa Ba W’oscin (12″x16″ Philadelphia edition), Se Quo Yah (13.5″x19.5″ mat opening, sold Henry Southern, Books and Prints, London) and Red Jacket (13.5″x19.5″ [mat window], London Published by Campbell and Burns). If you could be of assistance I would be most grateful. Best wishes

Embry Clark says: May 12, 2020 at 2:31 pm

Hello Michael: Unfortunately, we don’t provide appraisal services. Best of luck!

Lee S Jacobs says: March 5, 2020 at 9:23 am

I have a third octavo edition of McKenney and Hall’s Indian tribes of North American. Printed in Philadelphia , T. K. & P. G. Collins for D Rice & A N Hart 1858. With some light foxing in the first volume. Some mild scuffing on the leather bindings. Is this edition in demand? What value would you place on it? I am interested in selling it.

Embry Clark says: May 12, 2020 at 2:24 pm

Hello Lee: Please feel welcome to direct any books to sell inquiries to [email protected].