The modest woodcut leads the way as the earliest form of printmaking in the Western world. While technically the simplest of all illustrative processes, it is also the most difficult to master. From its crude beginnings dating back to 1400 AD (and as far back as 220 AD in Asia), woodcuts evolved from the rudimentary (stamps depicting spiritual symbols) to the intricate artworks of brilliant illustrators such as Albrecht Durer.

Woodcuts fall into the “relief” category of printmaking, meaning that ink is deposited onto the surface of paper by the raised portions of the wooden block. Anything that has been whittled away during the carving process will appear as a white area. Artists carve into the plank side of the block of wood (historically, nut or fruit wood was a popular option), following the direction of the grain and pulling the knife towards the body. The blank areas peel away, leaving the outlines, which are later inked black.

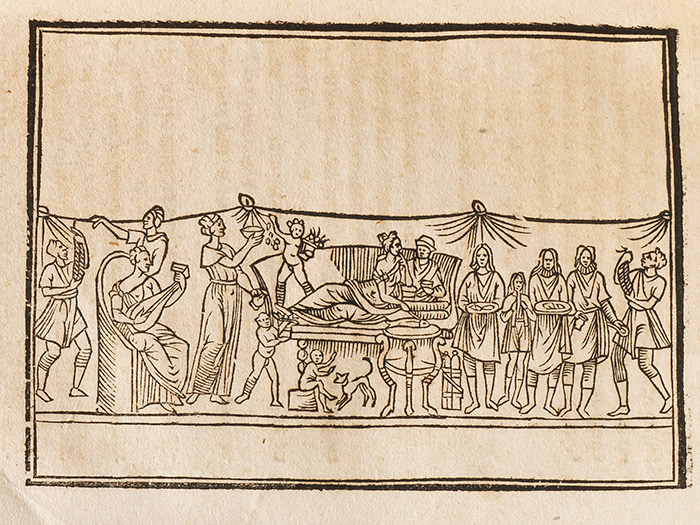

Generally, the artists who sketched the drawings differed from the craftsmen who carved the picture into the wood (the block-cutter). Early on, block-cutters would err on the side of caution when carving, favoring thick and often rough-edged outlines. Slicing wood portions too thin could cause pieces of the block to snap off under the pressure of printing. These early efforts resulted in flat, cartoonish pictures void of depth and shading. Color was sometimes added by hand after printing the outlines, but most examples remained black-and-white.

Given the limitations of this print technique and the quick rise of engraving–which allowed for much greater artistic freedom–woodcuts seemed as though they were beginning to become obsolete outside of their use for cheap souvenirs. But Gutenberg???s invention of moveable type changed that: woodcuts, it turned out, had a meaningful and quite practical place in the print world. Engravings had to be printed separately, whereas woodcuts could be fixed into place alongside text, thus creating the possibility of harmonizing text and picture into a single work. Woodcuts evolved. Woodcut illustrations became a crucial and much-valued part of telling a story.

As printed materials began to spread, the woodcut process became more refined. Line work began to vary in thickness and carvings became more detailed. However, even though great artistry began to emerge, few 15th-century woodcut artists had their work credited. Today, their identities remain a mystery.

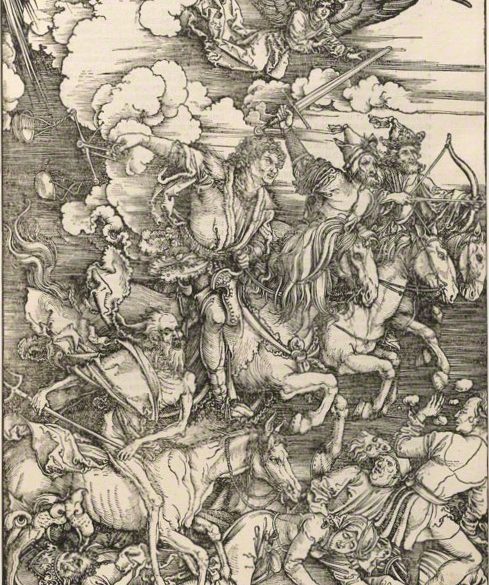

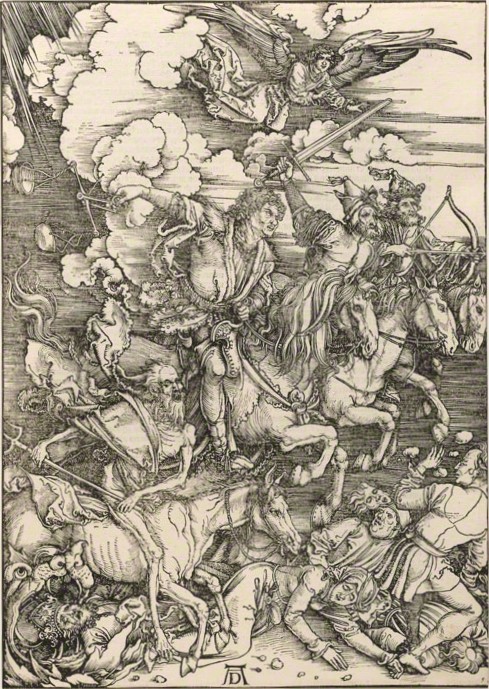

Nevertheless, there are a few notable names that helped elevate the unsophisticated woodcut into a magnificent form of artistic expression. In particular, the German artist Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) stands apart as master of the craft. He began his studies as an apprentice working on the epic Nuremberg Chronicle, printed in 1493. The work featured over a thousand woodcuts, and it is believed that Durer may have assisted with a few of the illustrations. Durer would go on to be proficient in several different illustrative processes, including engraving, but his most iconic work is a series of woodcuts depicting The Apocalypse from the Book of Revelations. His Four Horsemen plate encompasses all of his skills as an artist???depth, tone, symbolism, and motion–all achieved within one of the most restrictive illustration methods.

Upon brief examination, it may seem impossible to discern the difference between a highly skilled woodcut and engravings. However, even the most masterful of woodcuts will still display some standard characteristics of the process. Telltale giveaways include uneven thickness of the inked outlines, rough black frames that surround the illustration, and irregular ink distribution that appears splotchy or lighter in certain areas. Woodcuts also lack intuitive line work, meaning a close examination of the print will reveal lines joined together in a very deliberate manner as opposed to the fluidity of movement in a sketch, engraving, or etching.

While engraving and etching would be favored into the 16th century and beyond, illustrators still returned to woodcuts for their stark simplicity and boldness. Artists such as Rudyard Kipling, William Nicholson, and Vanessa Bell (Virginia Woolf???s sister) used the process into the 20th century with great success.