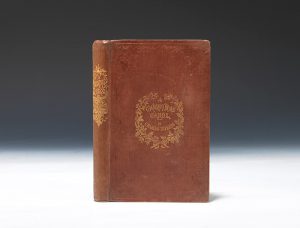

When you call someone a ???scrooge,??? most people understand you to mean someone who is miserly, uncharitable, selfish, and just generally unfriendly. Most people also know that ???scrooge??? stems from Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens??? A Christmas Carol.

It???s a classic example of how the literary becomes everyday. There are plenty of other examples that I didn???t realize stemmed from canonical texts until I became a bookseller. Here are some I???ve come across in the last few years.

Man from Porlock

In 1797, while in the midst of what was likely an opium-induced dream-state haze, Samuel Taylor Coleridge began to compose his poem ???Kubla Khan.??? As he committed his vision to paper, Coleridge was interrupted by a knock at the door. The unexpected visitor, a man from the neighboring village of Porlock, detained Coleridge for over an hour. By the time the poet returned to his poem, the dream-vision had faded, and he was left with only a fragment of his intended opus.

There???s some debate among scholars about the veracity of these events. Nevertheless, ???man from Porlock??? (or more simply ???Porlock???) has entered the vernacular to mean ???an unwanted guest.???

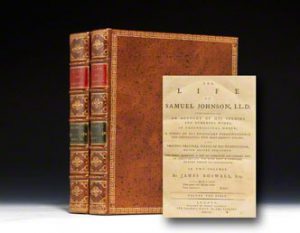

Boswell

James Boswell (1740-1795) is best remembered for his 1791 biography Life of Johnson. The book chronicles the life and work of the ever-curmudgeonly Samuel Johnson, who in turn is best remembered for his 1755 Dictionary of the English Language, the progenitor for just about every English-language dictionary that has since followed.

So encompassing and revolutionary was Boswell???s biography that his name has entered the vernacular to mean ???a person who records in detail the life of a usually famous contemporary.???

Bonus fact: For any BBC Sherlock fans, Season One???s ???I???d be lost without my blogger??? dialogue is pulled from Arthur Conan Doyle???s original Sherlock Holmes story ???A Scandal in Bohemia,??? in which Sherlock comments to Watson, ???I am lost without my Boswell.???

Proof is in the pudding

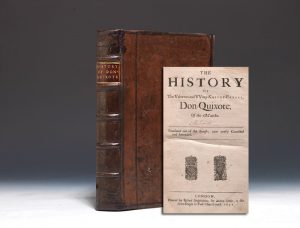

The most common complaint about this proverb is that it doesn???t make sense. And, in fact, it doesn???t make much logical sense–until you know that the original sentiment was ???the proof of the pudding is in the eating.??? Oxford scholars locate the proverb???s origins in a 14th century epic devoted to Alexander the Great (???Jt is ywrite that every thing Hymself sheweth in the tastyng???). Others cite William Camden???s 1605 Remains Concerning Britain. The more ???modern??? incarnation, however, is often attributed to Cervantes??? Don Quixote, which was also first published in 1605.

In the original sense, ???proof??? was understood as a kind of test, and ???pudding??? was generally understood as a dish more akin to blood sausage or shepherd???s pie. In a literal sense, the only way to know if a dish would make you ill was to eat it. That said, the phrase has entered the vernacular to mean ???the result is its own conclusive evidence.???

Hodgkinsonne for A. Crooke.

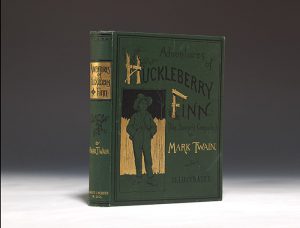

I???ll be your Huckleberry

The origins of this phrase ??? made famous in more recent years by the movie Tombstone ??? are even more convoluted.

Upon arriving in America, early European settlers encountered flora and fauna they???d never seen before. One such example was a small, dark berry that the settlers called hurtleberry, which eventually morphed into huckleberry. For many years, the term huckleberry was used figuratively to connote something small and insignificant ??? a tad, a skosh, a wee bit.

In interview from the 1890s, Mark Twain cites this figurative understanding as his reason for choosing the name Huckleberry for his most famous character. He wanted to instill from the outset the notion that Huck was of a ???lower extraction??? than Tom Sawyer.

At some point, however, the term shifted into a kind of affectionate (if still slightly pejorative) term for an assistant or sidekick. From here, it???s not so long a leap to I???ll be your huckleberry, meaning “I???m the one for the job.”

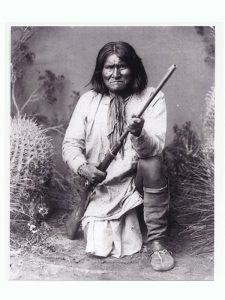

Geronimo!

Recently a conversation with a colleague brought up the question: Why do people yell Geronimo before they jump off a cliff? Turns out the origin, while not strictly literary, is unexpectedly humorous.

In 1940, in the early days of Army parajumping, a group of 50 soldiers came together to form the Parachute Test Platoon. The most popular story goes that on the eve of their first mass jump, the men took in a movie: Geronimo. At some point, the group began hassling one Private Aubrey Eberhardt, who claimed he wasn???t nervous at all. To prove he wasn???t terrified while jumping, Eberhard told his buddies that he would shout ???Geronimo!??? as he leapt from the plane.

In another version of the story, a popular radio song about Geronimo was a source of inspiration for the Test Platoon.

Comments

7 Responses to ““I’ll be your Boswell”: Words Coined From Literary Classics”

Matt says: February 21, 2014 at 6:47 pm

Very informative about all you write about and Charles Dickens A Christmas Carol has become one of the rarest books to find. small limited I have many 1st edition 1st print dickens as been fan of dickens for years but have not come across 1st edition 1st state/print for sale or even to look at unless you got a millionaire bank account A Chrismas carol is my quest to find. Thanks for your great write ups and passion for books, Only started to become so serious and addicted about books from reading Your website and guide on books thanks again Matt.

Embry Clark says: February 22, 2014 at 6:17 pm

Thanks, Matt! Glad to hear you enjoyed the post. Glad, too, to know that both the BRB website and blog have proved helpful in your own collecting. Dickens’ Christmas Carol is, as you say, a very tough book to find. That said, we do currently have an excellent first edition, first issue in the original cloth on display in our Las Vegas gallery. If you find yourself in town, swing by to take a look!

Matt howard says: February 23, 2014 at 2:11 pm

Thank you so much for letting me no about paperback version. I only collect Antiquarian hardback I have a later hardback copy that is for reading as I would never read the original if I can find reprinted copy I have the other four in the collection that would be my Defining moment in collecting Dickens books. I will retire that day Finnish any and everything I was doing sit on a beach somewhere happy and complete. Thanks againg Matt

Matt says: February 23, 2014 at 4:27 pm

Hi Embry I was wondering but forgot to ask you who your favorite author is thanks Matt Howard.

Embry Clark says: March 2, 2014 at 6:34 pm

Hi Matt: That’s always a tough question – usually with a long answer. At the top of the list I’d have to put Bruno Schulz, Raymond Chandler, and Lorine Niedecker. It’s harder to pinpoint a favorite book, but Shakespeare’s “Othello” and Janet Kauffman’s “The Body in Four Parts” are certainly up there.

Claire Martino says: December 13, 2021 at 6:55 pm

What about ???And Bob???s your uncle!

Jennifer says: March 31, 2022 at 2:37 am

And Fanny???s your aunt!