In Part 1, I introduced you to George Mason and his 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights and Virginia Constitution, and their extraordinary influence on the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights. Mason wrote in 1778:

We have laid our new Government on a broad Foundation, & have endeavoured to provide the most effectual Securities for the essential Rights of human nature, both in Civil and Religious liberty; the People become every Day more & more attach???d to it; and I trust that neither the Power of Great Britain, nor the Power of Hell will be able to prevail against it.

But his work wasn’t finished.

In 1787, Mason served as a Virginia delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, where he was one of the most frequent and influential speakers. Mason fought vigorously to defend the rights of the people and the states, and he believed the proposed Constitution gave too much power to the federal government and ???would end either in monarchy, or a tyrannical aristocracy.??? Though he was a slaveholder, he sought to end the slave trade in America and opposed a provision allowing it to continue until 1808.

But his most crucial objection was that the Constitution didn???t have a bill or declaration of rights. Mason???s proposal to include one was defeated, as was his proposal to hold a second convention to revise the Constitution because ???this Constitution had been formed without the knowledge or idea of the people. A second Convention will know more of the sense of the people, and be able to provide a system more consonant to it.??? The convention instead voted to submit the Constitution to the states for ratification.

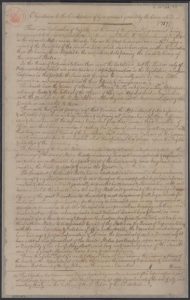

The Library of Congress??? copy of Mason???s Objections to the Constitution, from Washington???s papers. Courtesy Library of Congress, Digital ID# US0064.

Mason refused to sign the Constitution, having declared ???I would sooner chop off my right hand than put it to the Constitution as it now stands.??? On September 16th, Mason wrote down his Objections to the Constitution, which began:

There is no Declaration of Rights, and the laws of the general government being paramount to the laws and constitution of the several States, the Declarations of Rights in the separate States are no security…There is no declaration of any kind, for preserving the liberty of the press, or the trial by jury in civil causes; nor against the danger of standing armies in time of peace.

Mason sent copies of his Objections to many people in an effort to persuade them, including his friends Washington, Jefferson, and Madison. The document was widely circulated and reprinted in newspapers and as a pamphlet. ???There is no Declaration of Rights!??? became a rallying cry among the anti-Federalists who opposed ratification of the Constitution as well as those who supported the Constitution but wanted the rights of individuals and states clearly defined and guaranteed.

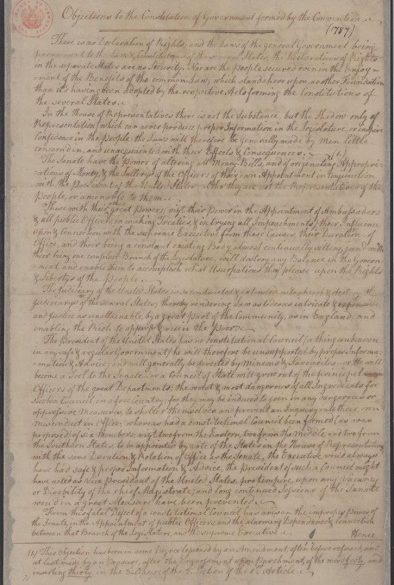

The Library of Congress??? copy of Mason???s October 7, 1787 letter to Washington enclosing his Objections to the Constitution. Courtesy George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, Series 4, Image 266.

Historian Robert Rutland noted:

From the opening phrase of his ???Objections??? to the bill of rights that James Madison offered in Congress two years later, the line is so direct that we can say Mason forced Madison???s hand. Federalist supporters of the Constitution could never overcome the protest created by Mason???s phrase: ???There is no Declaration of Rights.??? Months later, Hamilton was still trying ???to kill that snake??? in Federalist No. 84??? But the idea was too powerful??? Not long after Mason???s pamphlet reached Jefferson???s desk in Paris the American minister was writing to friends at home in outspoken terms. Jefferson told Madison he liked the Constitution but was alarmed by ???the omission of a bill of rights???.???

Jefferson described the bill of rights as something that ???the people are entitled to against every government on earth??? and [that] no government should refuse.”

The Library of Congress??? copy of Madison???s October 18, 1787 letter to Washington criticizing Mason???s Objections to the Constitution. Courtesy George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, Series 4, Image 287.

Madison commented that Mason left Philadelphia ???in an exceedingly ill humour indeed.??? Back home in Virginia, Mason fought against the unconditional ratification of the Constitution and wrote a list of proposed amendments and a Bill of Rights (based largely on his Declaration of Rights) for the Virginia ratifying convention. At a critical point when ratification by Virginia and New York was in doubt, Madison promised that a bill of rights would be added to the Constitution after ratification. Virginia, New York, and other states agreed to ratify but also submitted their proposed amendments.

In June 1789, Madison submitted to the new Congress his proposed amendments to the Constitution, drawn largely from the amendments proposed by the states and the Virginia Declaration of Rights. That September, Mason wrote to a friend:

I have received much satisfaction from amendments to the federal Constitution that have lately passed the House of Representatives. I hope they will also pass the Senate??? With two or three further amendments??? I could cheerfully put my hand and heart to the new government.

The federal Bill of Rights was finally ratified on December 15, 1791.

With such important contributions to America???s founding documents, how did Mason become a ???Forgotten Founder???? His fierce public battle against the Constitution and for a Bill of Rights damaged his reputation and his friendships with Washington, Madison, and other powerful Federalists. Rutland noted that Mason was ???a reluctant statesman??? and ???that rare type of public man who disdains personal power.??? He refused appointments to the Continental Congress and U.S. Senate. Mason biographer Jeff Broadwater noted that he didn???t ???seek the historical spotlight??? and never wrote his memoirs. He died at the age of 66 in 1792, less than a year after the Bill of Rights was added to the Constitution.

Comments

One Response to “Forgotten Founders: George Mason, Part 2???1787”

David E. Young says: January 14, 2018 at 11:54 am

An excellent short analysis of George Mason’s role in supporting a Federal Bill of Rights.