When I visited Walt Disney World, one thing I really wanted to do was tug at the Sword in the Stone, right next to the Fantasyland carousel. I’d heard the sword remains locked in place most of the time, but that every now and then, for some lucky visitors, it pulls free. Alas, it stayed stuck for me, dashing any hopes I had of being hailed the “rightwise ruler born of England.”

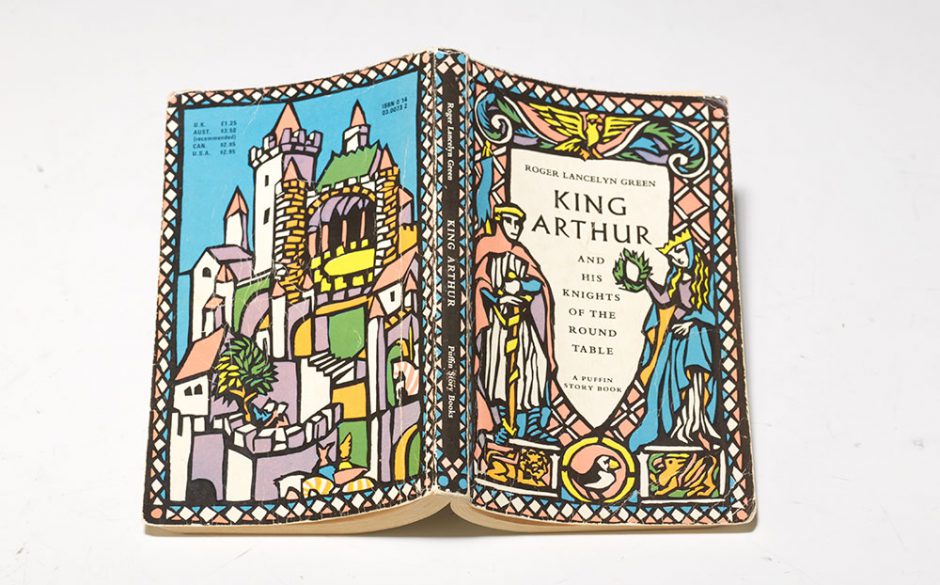

I’ve loved Arthurian legend since I was ten. A relative visiting from Britain brought me a Puffin paperback edition of Roger Lancelyn Green’s King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table (originally published 1953). Despite the toll decades of re-reading have taken on that book’s covers and spine, it sits proudly on my shelf, one of the few books from childhood I still own. Green’s crisp and evocative text and Lotte Reiniger’s intricate, woodcut-like illustrations can still stir my sense of wonder and carry me off to Camelot.

At Bauman Rare Books, we believe all books are, in some sense, magical. But I think Arthurian books conjure more magic than most!

Centuries of authors and artists have drawn inspiration from the “Matter of Britain,” leaving rich treasures for rare book collectors to delight in. A fine library devoted to Arthurian legend transcends bibliographic boundaries. It includes poetry and prose. It spans history, hagiography, archaeology, even satire. It embraces everything from fairy tale to historical fiction. But each volume in an Arthurian library offers some insight into why these stories continue to enchant the world.

The Sword in the Stone: T.H. White’s “Wish-Fulfillment”

For example, consider again that sword in the stone. It’s an iconic part of Arthur’s mythos today, but it didn’t first appear until the late 12th century. French poet Robert de Boron included the episode in his work, Merlin.

It’s not hard to see why almost every Arthurian tale-teller since has included it, too. The miraculous means by which young Arthur wins his throne—repeatedly drawing out the sword until even the most hardened skeptics are satisfied—validates the hope that, sometimes, the little guy wins, and things happen as they should.

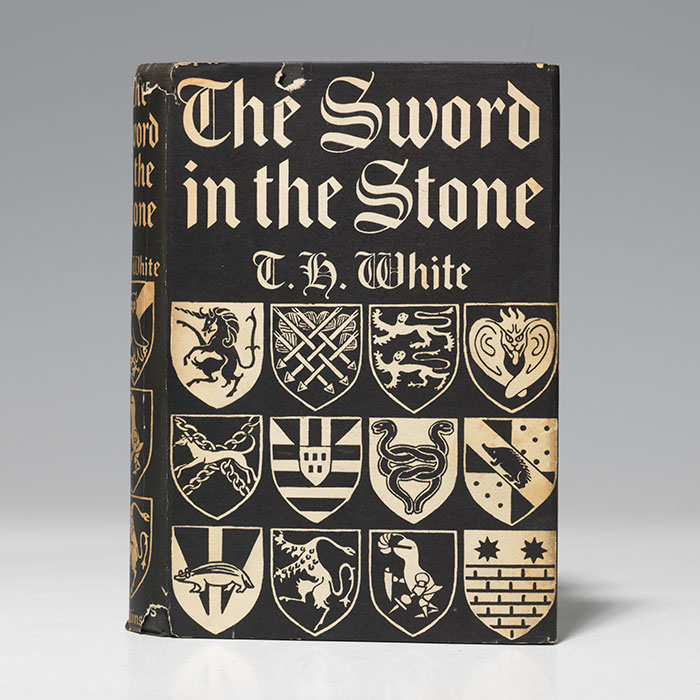

Things did not happen as they should have for young Terence Hanbury White. Neglected by soon-to-be-divorced parents, beaten by a housemaster at his boarding school, sick with tuberculosis—White endured a childhood that left mental and emotional scars. When he wrote The Sword in the Stone (1938), then, he wrote “a kind of wish-fulfillment of the kind of things I should have liked to have happened to me when I was a boy.”

In White’s book, the wry old wizard Merlyn tutors “the Wart” (young Arthur’s nickname) by transforming him into a fish, an ant, a wild goose, and other animals. The Wart learns lessons about humanity’s problems and potential, lessons that serve him well when his moment of truth arrives and he begins his reign. White imagined Arthur’s education to be a wonder-filled exposure to the world that he had been denied.

White revised The Sword in the Stone to make it the first part of The Once and Future King (1958), his Arthurian tetralogy. This larger work is, as scholar Maureen Fries states, “undoubtedly the finest [achievement] in 20th-century Arthurian prose.”[3] But necessarily, it grows darker in tone as Camelot starts to crumble, and the later books’ gathering gloom casts some small shadows back over the revised first one.

In its first edition form, however, The Sword in the Stone is a captivating fanatsy from start to finish. Brimming with wit and warmth, punctuated by keen insights into human nature, and embellished with White’s own whimsical line drawings, the book demonstrates Arthurian legend’s ability to make us believe childhood wishes can come true.

Geoffrey of Monmouth: Making Sense of History

If an historical Arthur ever existed, he was a sixth-century chieftain who helped Britons hold back the tide of Saxon invaders. In his Historia Brittonum (circa 830 CE), a Welsh monk named Nennius makes the earliest known reference to Arthur by name. Nennius’ Arthur is not a king, let alone a fully developed character; but even in this earliest appearance, he is larger than life. Credited with winning a dozen battles against the barbarians, this Arthur is an ancient Welsh Samson, single-handedly slaughtering almost a thousand foes in one day.

Three centuries later, Welsh bishop Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote his Historia regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain). The cleric’s chronicle doesn’t live up to modern academic standards. As author Mary Stewart explains (in the afterword to her 1970 Arthurian novel, The Crystal Cave), Geoffrey was “arranging his facts to suit his story, and when he got short on facts (which was on every page), inventing them out of the whole cloth.” But despite its many factual faults, the Historia’s successes as literature and national myth ensured its survival.

Geoffrey shapes an account of British history that, much like the Bible’s history of ancient Israel, interprets a succession of rulers—some good, others bad—as evidence of God’s hand working both doom and deliverance for a chosen people. The story reaches its climax with Arthur, who here more closely resembles the monarch of later literature. He is conceived thanks to the magic of the seer Merlin. He holds court amid luxury and chivalry that “far surpassed all other kingdoms” (especially France, a kingdom he spends a good deal of the text conquering). And he is ultimately betrayed in battle by Modred, before being carried to the isle of Avalon for the healing of his mortal wounds.

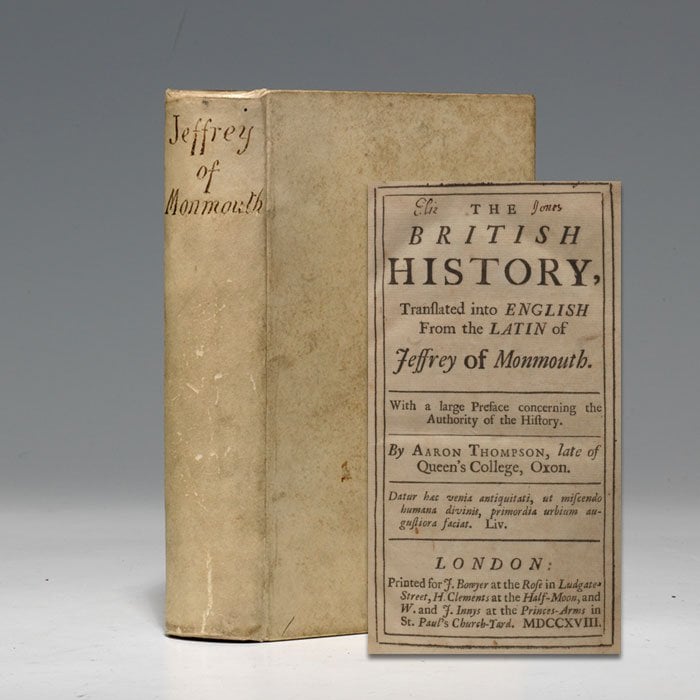

Geoffrey’s Historia portrays the Britons as a civilization with a proud past and a great destiny, and his book proved one of the Middle Ages’ most important. Various monarchs, as late as James VI of Scotland, used Geoffrey’s text to justify claims to the throne. The book also provided Shakespeare his source material for King Lear. But the Historia went untranslated into modern English until the 18th century, when Aaron Thompson published The British History (1718). Thompson was domestic chaplain to noted architect Richard Boyle, but his real claim to fame is reintroducing Geoffrey to English readers. He knew not everything Geoffrey wrote was factual; all the same, he respected his source as “a pleasant, and in many Places a true History of a very brave People.”

As Sheila Brynjulfson wrote, “Geoffrey is the reason why nearly everyone in the western world knows who King Arthur is. It was he who lit the romantic literary flame, and European writers had a field day with it.” As we’ll see in Part Two, Geoffrey of Monmouth wouldn’t be the last author to use Arthurian legend to make sense out of sometimes seemingly senseless history.

What was your first exposure to Arthurian legend? Let us know in the comments below.

Comments

2 Responses to “Collecting Camelot: Rare Arthurian Books”

ROGER TREGLOWN says: August 28, 2015 at 5:46 am

“A fine library devoted to Arthurian legend transcends bibliographic boundaries. It includes poetry and prose. It spans history, hagiography, archaeology, even satire. It embraces everything from fairy tale to historical fiction. But each volume in an Arthurian library offers some insight into why these stories continue to enchant the world” – indeed so. Last year I bought the Library of the late Professor Fanni Bogdanow ( 1928 -2013 ) Lecturer in French in the University of Manchester and one of the leading Arthurian Scholars in Europe. The collection included her working papers, her Student’s Theses, and academic ‘ Arthuriana books ‘ not only in English, many with her notes and marginalia.

Mike Poteet says: September 1, 2015 at 4:26 pm

Professor Bogdanow’s collection certainly sounds like a fascinating one! Thanks for reading and commenting.