In the decade or so following his disastrous-if-heroic Coppermine Expedition to the Arctic, John Franklin kept fairly busy. Upon his return to England, he married and became first a father and then a widow in relatively short order. He journeyed into the Arctic twice more, married a second time, received a knighthood (twice), and served as the Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen???s Land (Tasmania).

By 1845, though much of the Arctic coastline had been successfully explored, several hundred kilometers of those coastal regions remained uncharted. The Admiralty decided to launch an expedition that would at last ???complete??? the Northwest Passage. After much deliberation ??? and the refusal of his first several choices ??? Sir John Barrow, Second Secretary of the Admiralty, offered the command to 59-year old John Franklin.

And here???s where the tragedy and mystery of Franklin???s legacy finally begins to unfold.

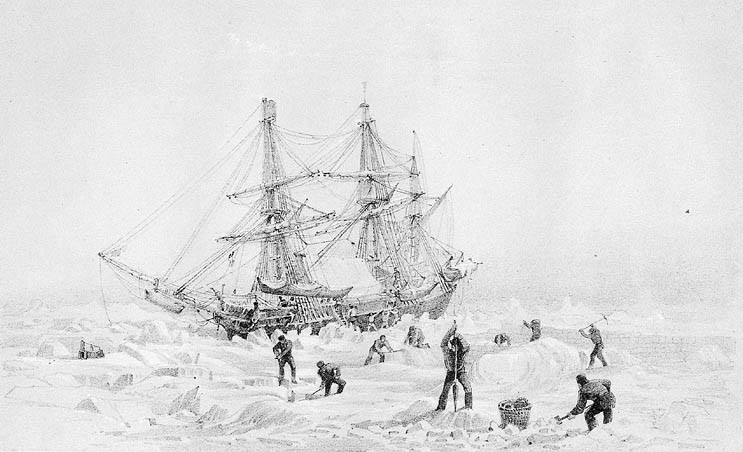

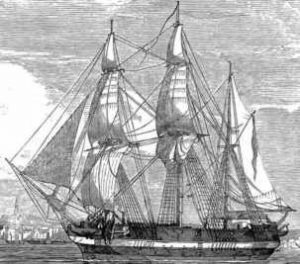

The expedition consisted of two ships, Terror and Erebus, which were outfitted with the latest technology. The ships boasted steam engines, iron-reinforced hulls, and heated cabins. Of equal importance, they were equipped with 3-5 years (sources vary) of food stores. (Presumably, Franklin was especially sensitive to the specter of starvation after his previous Arctic experiences.) And so it was that on May 19, 1845, 134 men set sail on what was almost certainly (at the time) the best-equipped British-launched polar expedition ever.

Bonus fact: Both Erebus and Terror had already sailed into polar regions by the time Franklin launched his final expedition. In 1841, under the captaincy of James Clark Ross, the ships traveled to Antarctica, where (among much else) Ross named two volcanoes in their honor.

In July, the party briefly made port in Greenland, taking on additional supplies. Several sailors were discharged for various reasons, bringing the total number of men to 129. Most of the remaining crew wrote letters home. Sprinkled among these messages are small details of life under Franklin???s command ??? he apparently banned swearing and drunkenness, for instance. (Only polite sailors need apply.)

Terror and Erebus were sighted by whaling ships in Baffin Bay at the end of July. It was the last time any member of Franklin???s crew would ever be seen alive. Indeed, Franklin???s final expedition would come to be immortalized as the Lost Expedition.

Stay tuned for Part IV, where the British Admiralty, Lady Franklin, and even a few Americans spend the next 30 years searching the Arctic and piecing together the mystery of how and why Franklin???s expedition failed so terribly.