Welcome to “Culture Beat,” a new series inspired by current events and exhibitions around New York City. Check out these shows while you’re in town, and then continue the conversation with us in our gallery!

Every series needs an epic origin story at its beginning, and fortunately, the Morgan Library was kind enough to oblige us this month. Their new summer exhibition, “William Caxton and the Birth of English Printing,” is well worth a visit before it closes on September 20.

If you ever want to see a bookseller go into full “nerd mode,” just ask them about William Caxton. Gutenberg may get the credit for introducing movable type to Europe, but it was the business-savvy Caxton who brought this revolutionary technology across the Channel and launched English bookselling. By the end of the fifteenth century he had printed the first book in the English language (Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, printed on his first press in Bruges), the first book printed in England (Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales), and more than one hundred other titles, many his own translations of earlier works.

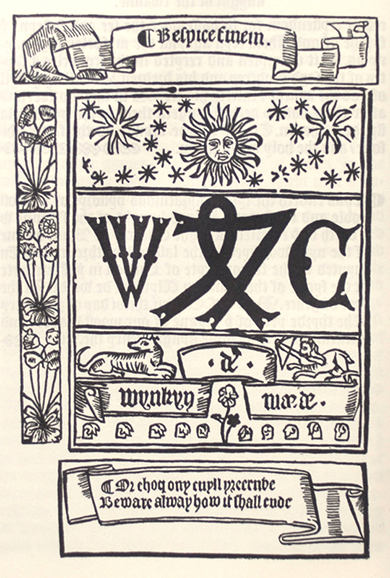

Caxton imprints are extraordinarily collectible today, and equally difficult to acquire. Originals may be out of reach for most of us, but a number of beautiful facsimile editions of his books have been printed over the years. This one, printed in 1976, was based on a copy of Caxton’s Reynart the Foxe owned by the great 17th-century diarist, Samuel Pepys. (BRB 83721)

Overachiever that he was, Caxton also did something else remarkable along the way: he began to standardize the unruly English language for the first time.

Was all of this the work of a heroic visionary out to change the world? Nope—Caxton was just a smart entrepreneur who knew how to sell. In an effort to build a brand with broad appeal, Caxton’s translations struck a balance between the major English dialects in use at the time (though one heavily weighted toward the vocabularies of his London customers).

Along with his books, Caxton’s English saturated the market. He never quite managed to iron out every quirk of vocabulary and spelling, but the precedent he set was an important first step toward a common linguistic and literary identity in England.

By the end of his life, Caxton’s “brand” was so well-known that his apprentice and successor, Wynkin de Worde, decided to adapt it for his own use. Top: Caxton’s printer’s device in facsimile from Reynart the Foxe (BRB 83721). Bottom: Wynkin de Worde’s device from The History of Helyas, photographed from a 1901 limited facsimile edition issued by the Grolier Club (BRB 88366).

But Caxton’s press is only the first chapter in a much longer story. In the century after his death, publishing in England and across Europe flourished. New vocabulary and ideas swept across borders on the printed page, fueling a scientific revolution and an explosion of new literature during the English Renaissance.

If you’ve ever been “at your wit’s end,” tried to get to “the root of the matter,” or seen “the writing on the wall,” you’ve already felt the influence of one of the towering literary achievements of this period: the King James Bible.

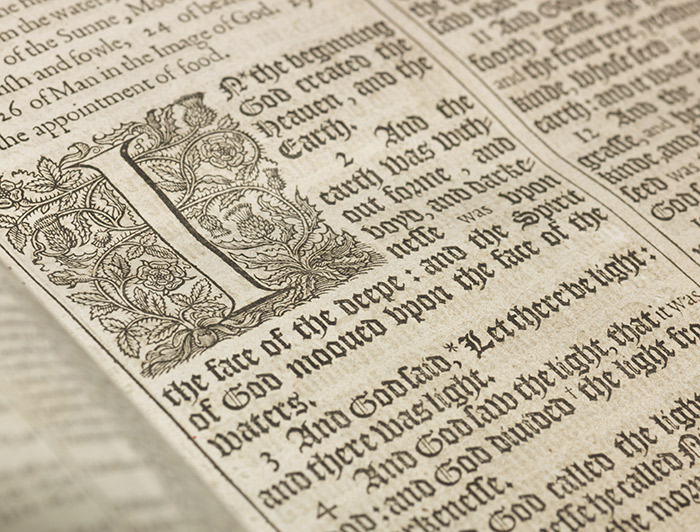

“And God said, Let there by light: and there was light.” From the 1611 King James Bible (BRB 104314)

In the grand scheme of book collecting, the King James Bible is an unusual prize. It’s not really a “first”—not the first English Bible (that distinction belongs to Wycliffe’s illicit fourteenth-century manuscript Bibles), nor the first printed English Bible (that would be Tyndale’s translation in 1526), nor even the first authorized English Bible (actually Myles Coverdale’s “Great Bible,” produced for Henry VIII in 1538).

(You can read more about all of these early English Bibles here.)

By the time the King James Bible arrived on the scene in 1611, all of these earlier translations and a number of others were crowding the field, making it difficult for English rulers to control their subjects’ understanding of the Word.

Instead of a first, the King James Bible was a great synthesis of scholarship and prose intended to surpass all competition. It was also an impressive feat of translation, undertaken by a team of forty-seven religious authorities appointed by James I. (Just imagine those committee meetings! “Be horribly afraid,” indeed.) The team re-translated much of the text from the original Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, and Latin, but it also borrowed heavily from previous versions of the Bible, especially Tyndale’s, preserving their most eloquent turns of phrase for future generations.

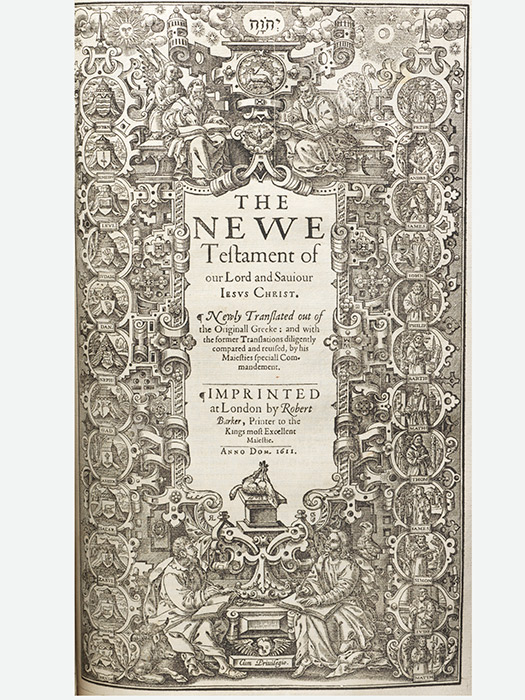

Title page of the 1611 King James Bible (BRB 104314)

It took a few years for King James’s version to catch up to the popularity of the earlier field of translations, but within a century it had reached more households than any other English book, giving regions with broad cultural differences a shared literary touchstone. It also injected more than two hundred idioms into spoken English, many of which are still hanging on today—and not just “by the skin of their teeth.”

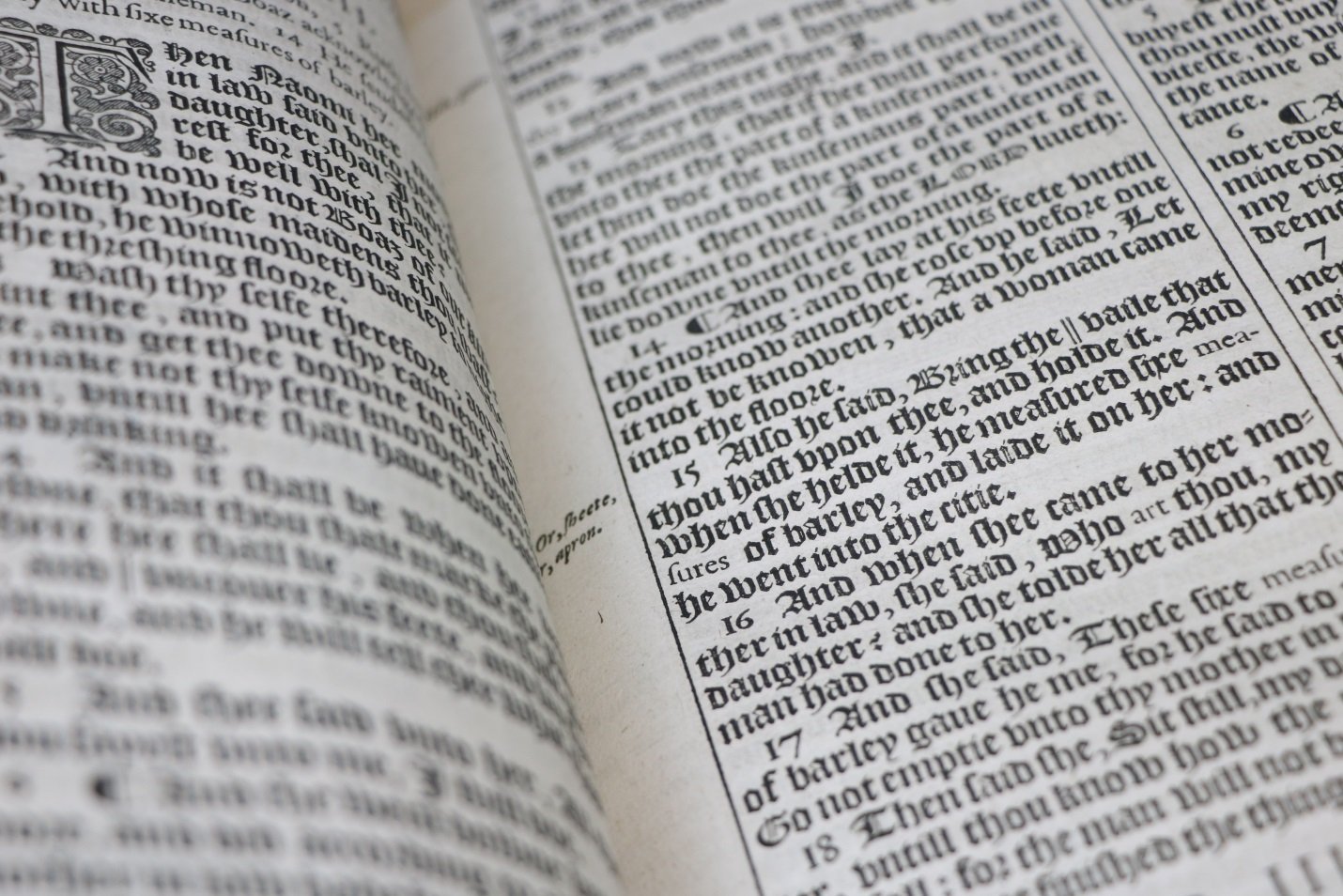

Once King James’s translation was complete, the pressure was on to put a copy into as many hands as possible. Royal printer Robert Barker put at least two presses into motion simultaneously, working from two master copies to print the massive tome faster. In the process, he inadvertently created two issues of the first edition. These so-called “He” and “She” Bibles are named for a variant printing of Ruth 3:15 that reads “and he/she went into the citie.” (BRB 104314)

By the mid-eighteenth century, printed English was sophisticated, comprehensible, and in great demand—but it lacked a gold standard. Primitive dictionaries existed, but nobody had ever looked closely at what the English language was, or how English words were being used in literature. Without a set of common rules, differences in spelling and the usage of words abounded, sometimes even within the same book.

Enter Samuel Johnson.

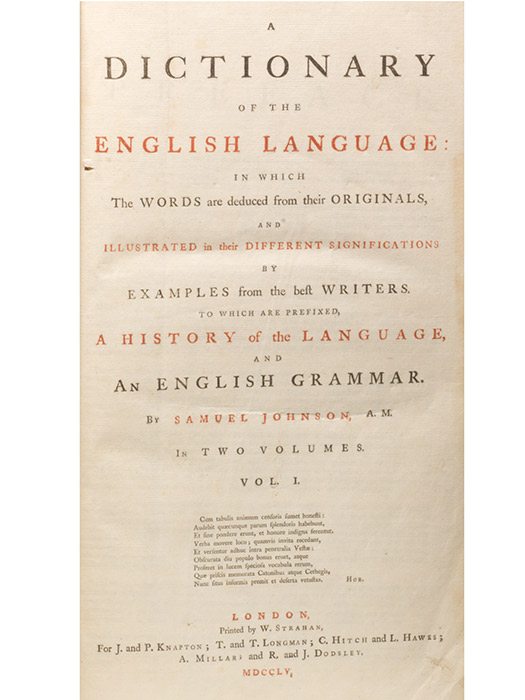

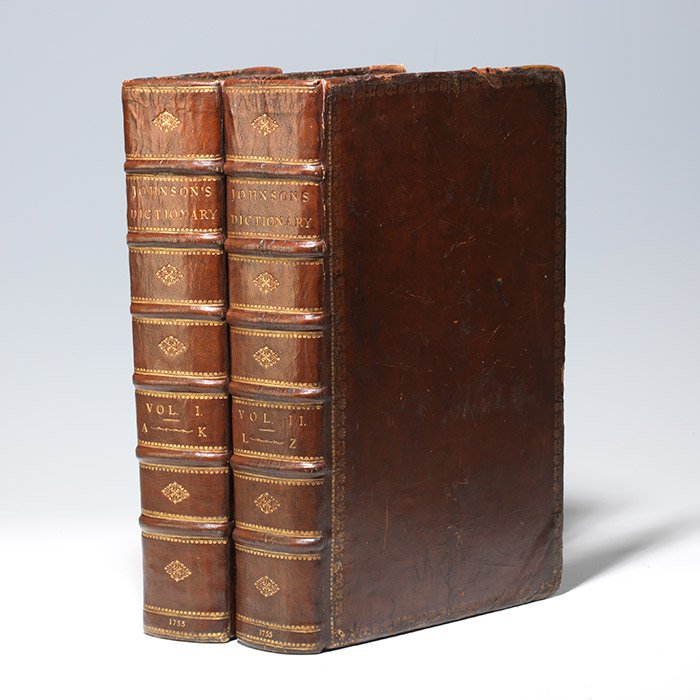

Title page of the 1755 first edition of Johnson’s Dictionary (BRB 103003)

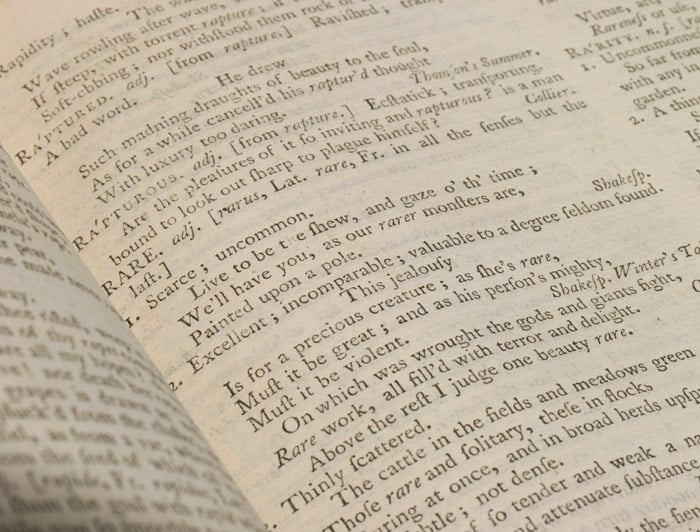

Johnson didn’t just compile a list of English words, or even a list of definitions already in use—the man sat down at his desk and wrote the English dictionary. For nearly nine years, he composed his own definitions of some 40,000 words, reported their origins, and tracked their usage by great writers to triangulate a precise understanding of the English lexicon.

After he completed the project in 1755, Johnson’s dictionary was more than just a useful tool for writers; it was an entertaining read, as well. A few of my favorite Johnson definitions include:

Patron: “One who countenances, supports or protects. Commonly a wretch who supports with insolence, and is paid with flattery.”

Oats: “A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.”

And of course:

Dull: “Not exhilaterating [sic]; not delightful; as, to make dictionaries is dull work.”

For readers, Johnson’s dictionary was anything but dull. His witty definitions were popular with writers and critics, but the project presented a problem for booksellers: with roughly 40,000 definitions, it was just too big to print cheaply. Nevertheless, the first edition was followed by numerous others, usually issued in small print runs. Dr. Johnson would have the final word on the English language for over a century, until the Oxford English Dictionary came along in 1888.

Containing roughly 40,000 entries, the first edition of Johnson’s Dictionary was a massive undertaking for printers and an expensive prospect for book-buyers, but also a tremendous accomplishment. (For comparison’s sake, the earliest English dictionary, the 1604 Table Alphabeticall, contained only about 2500 words. Contemporary projects like the King James Bible contained roughly 12,000 different English words, while Shakespeare’s First Folio contains approximately 20,000 different words.)

“Rare” defined in the 1755 first edition of Johnson’s Dictionary (BRB 103003)

Despite all attempts to order it, English—like any language—is something alive and constantly evolving. As the pace of change seems to accelerate out in cyberspace, it’s fascinating to look back at these early moments when the language we know began to come together, and to wonder what’s coming next!