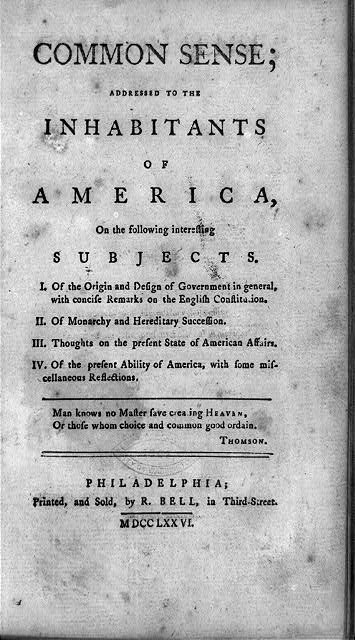

Should an independancy be brought about???, we have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest purest constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again.

??? Thomas Paine, Common Sense

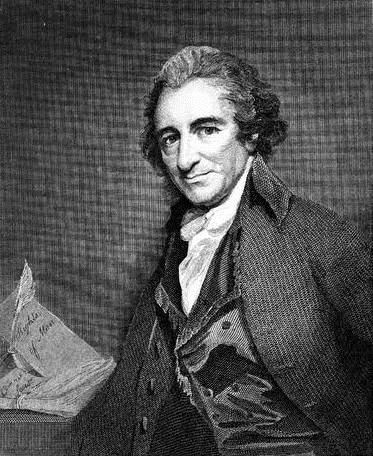

Want to start a fight between American history buffs? Just ask them whether Thomas Paine was a Founding Father.

It???s a surprisingly contentious question, as Paine continues to be one of history???s most controversial figures. Many insist he was not a Founder, for a hodgepodge of reasons:

- He wasn???t an American. (Paine was British by birth but American by choice???he emigrated in late 1774, swore an oath of allegiance to America in 1776, and became a citizen.)

- He wasn???t a Signer of the Declaration or a Framer of the Constitution, he never served in the Continental Congress or held political office, and he wasn???t a Revolutionary War hero.

- He was a dangerous radical, a revolutionary, an anarchist, a ???controversialist.???

- He was, in the words of Theodore Roosevelt, ???a filthy little atheist,??? rejected by his friends and hated by most Americans at his death. (???He had lived long, did some good and much harm,??? read a newspaper obituary notice. Only six mourners came to his funeral.)

Paine???s problem is that he didn???t die in 1792. Had he done that, his place among the pantheon of beloved founding fathers would have been assured,

noted Daniele Bolelli. Some disagree because Paine still wouldn???t fit their criteria. Paine???s talents were different from other Founders, as Eric Foner illustrated with this quote from Madame Roland: ???I find him more fit??? to scatter these kindling sparks than to lay the foundation or prepare the formation of a government. Paine is better at lighting the way for revolution than drafting a constitution.???

Let me state for the record that I do consider Paine to be a Founding Father, if for no other reason than without Common Sense America would not have declared independence in July 1776.

As Benjamin Franklin wrote to Paine:

You, Thomas Paine, are more responsible than any other living person on this continent for the creation of what are called the United States of America.

It was Franklin who changed Paine???s life by encouraging him to come to America and giving him a letter of introduction, and they remained friends until Franklin???s death.

Thomas Jefferson became another important friend and supporter of his works, as you can see in this 1792 letter to Paine:

I received with great pleasure the present of your pamphlets??? Would you believe it possible that in this country there should be high & important characters who need your lessons in republicanism, & who do not heed them?… But our people, my good friend, are firm and unanimous in their principles of republicanism & there is no better proof of it than that they love what you write and read it with delight… Go on then in doing with your pen what in other times was done with the sword.

Jefferson even commissioned a portrait of Paine to add to ???my pictures of American Worthies,??? a miniature painted by John Trumbull in 1788, which you can see on the Monticello website.

John Adams, however, famously hated Paine. Adams called him, among other things, ???a Mongrel between Pigg and Puppy, begotten by a wild Boar on a Bitch Wolf.??? Most of the celebrated Adams quotes praising Paine are taken out of context, like this quote from an 1819 letter to Jefferson: ???History is to ascribe the American Revolution to Thomas Paine!??? Adams is actually expressing outrage at the thought and calls Common Sense ???a poor, ignorant, malicious, short-sighted, crapulous mass.???

Some of America???s later heroes were great admirers of Paine, such as Abraham Lincoln, who constantly quoted his works. In 1877, on the 140th anniversary of Paine???s birth, Walt Whitman gave a speech about Paine, later printed in Specimen Days:

That he labor???d well and wisely for the States in the trying period of their parturition, and in the seeds of their character, there seems to me no question. I dare not say how much of what our Union is owning and enjoying to day???its independence???its ardent belief in, and substantial practice of, radical human rights???and the severance of its government from all ecclesiastical and superstitious dominion???I dare not say how much of all this is owing to Thomas Paine, but I am inclined to think a good portion of it decidedly is.

Thomas Edison considered Paine ???one of the greatest men of all time??? and ???our greatest political thinker.??? He wrote in his 1925 essay on Paine:

We never had a sounder intelligence in this Republic. He was the equal of Washington in making American liberty possible??? In ???Common Sense??? Paine flared forth with a document so powerful that the Revolution became inevitable.

Everyone, past and present, seems to have a strong opinion about Paine. But whether or not you believe he deserves to be called a Founder, you can???t ignore the extraordinary influence and importance of his writings, which I???ll explore in future posts, starting with Common Sense.

Comments

2 Responses to “Forgotten Founders: Thomas Paine, Part 1”

venecia [email protected] says: January 23, 2014 at 4:53 pm

when your a realist and very outspoken you have the least friend in this world so i guess he was one

Matt Szalwinski says: March 25, 2015 at 7:07 pm

I find John Adams’ remarks telling. According to historians, Mr. Adams’ cousin Samuel, like Paine, loved to stir things up. Sam Adams enjoyed antagonizing the British and the loyalist citizens of Boston through brash physical behavior, while Paine did so through his writings. It’s interesting to ponder whether John viewed the behavior of his cousin Samuel as patriotic or idiotic.