Looking to escape the summer heat? You can’t beat a blissfully cool day exploring MoMA???s current show, ???One-Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and Other Works.???

Jacob Lawrence???s masterful Migration Series stands as the exhibition???s fulcrum, narrating the dramatic exodus of nearly six million African-American men and women from the rural reaches of the Deep South into the hearts of industrial American cities in the early years of the twentieth century.

But the exhibition really takes off in the surrounding galleries, where you can explore the explosion of artistic innovation that followed. The Great Migration created fruitful urban enclaves of intellectuals, artists, writers, and musicians — most notably in Harlem in the 1920s, but also in other cities, and continuing into later decades. These artists??? lives and careers thrived as they alternately fed on each other’s ideas, and competed to articulate different visions of black experience and identity. What they had to say would influence American culture for years to come.

A number of collectible books survive from this era, though not all were purely literary. In fact, some of the greatest achievements of the Harlem Renaissance (or ???New Negro Movement,??? as it was known then) were collaborative projects or innovative literary experiments born out of this close contact between artists of different backgrounds and disciplines.

Here in Manhattan is not merely the largest Negro community in the world, but the first concentration in history of so many diverse elements of Negro life. It has attracted the African, the West Indian, the Negro American; has brought together the Negro of the North and the Negro of the South; the man from the city and the man from the town and village; the peasant, the student, the business man, the professional man, artist, poet, musician, adventurer and worker, preacher and criminal, exploiter and social outcast. Each group has come with its own separate motives and for its own special ends, but their great experience has been the finding of one another.

–Alain Locke, The New Negro, 1925

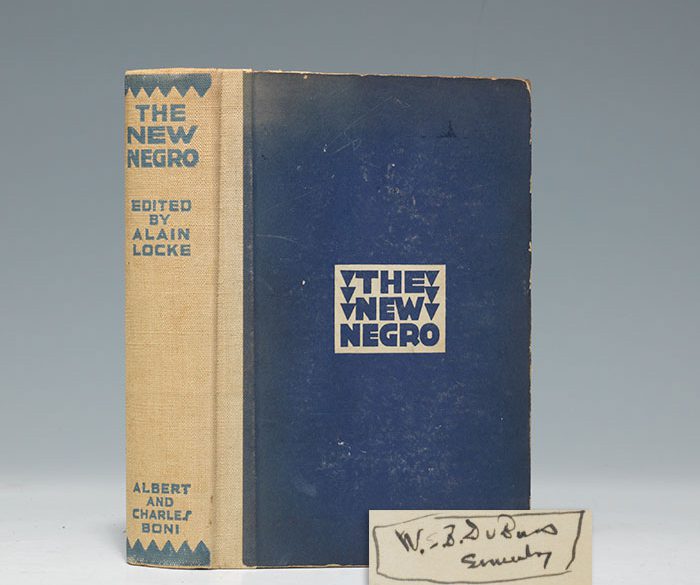

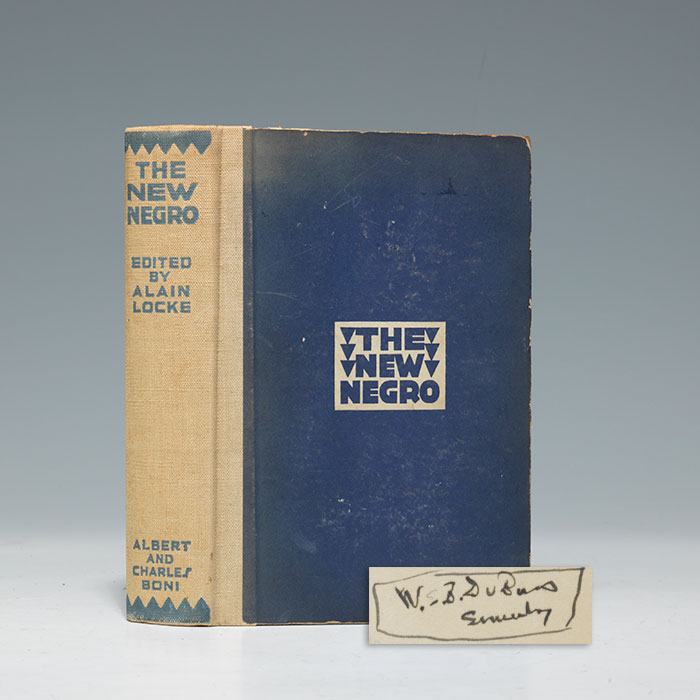

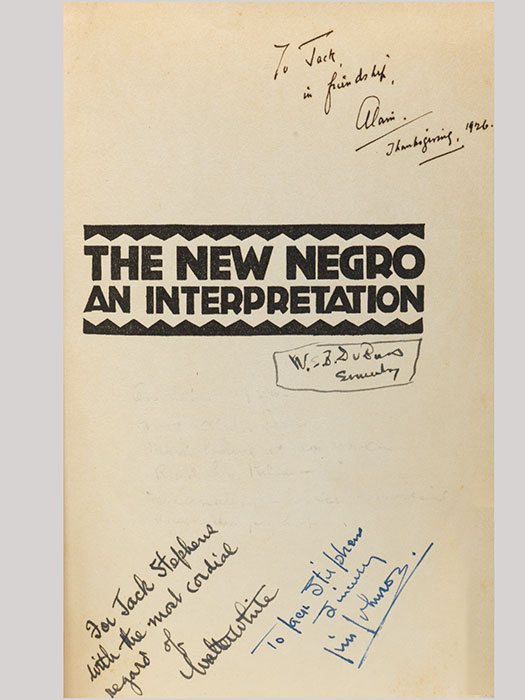

The most famous single title is perhaps Alain Locke???s 1925 anthology, The New Negro, which laid out both a name and a goal for the era. Throughout the 1920s, Locke had championed Harlem as a ???laboratory of a great race-welding,??? where black artists and writers could work together toward a common cause. Rejecting the persecution of the Jim Crow South and the shallow blackface caricatures of American minstrel traditions, Locke envisioned a new period of artistic achievement that would draw on the rich heritage of the African diaspora. (A similar international movement of N??gritude, driven primarily by Aim?? C??saire and L??opold Senghor, built on Locke???s ideas a few years later.)

As a book, The New Negro is thoughtful and lively. Locke brought together a wide variety of important voices (old and young, black and white) to contribute poetry, short fiction, and essays, from W. E. B. Du Bois, Claude McKay, and Langston Hughes to Countee Cullen, Zora Neal Hurston, and James Weldon Johnson. Even Albert Barnes, already well-known in 1925 for his avant-garde art collection on the outskirts of Philadelphia, stepped into the mix with an important early essay on African-American art.

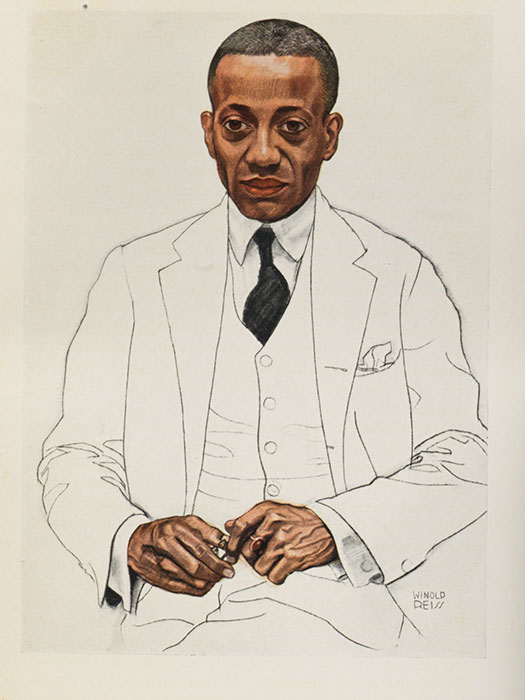

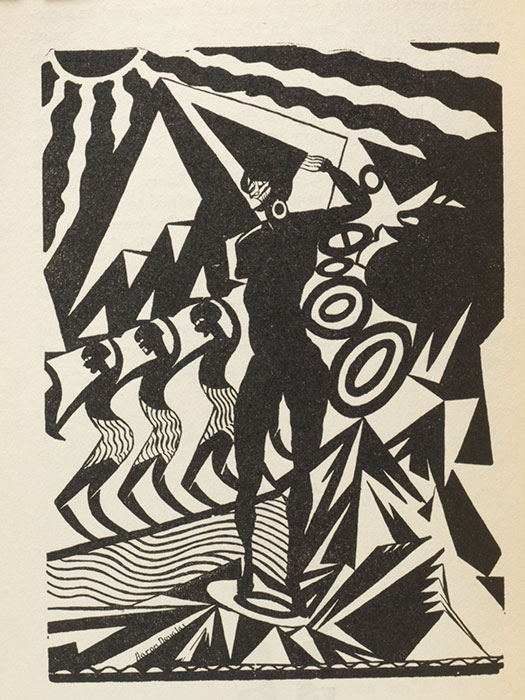

Beyond the written word, the book is peppered with bars of music, and profusely illustrated by a young Aaron Douglas and Bavarian artist Winold Reiss. All in all, it served as both a call to arms and a model of the sort of achievement Locke hoped to encourage: a polished, polyphonic project that was proudly racial, and undeniably modern.

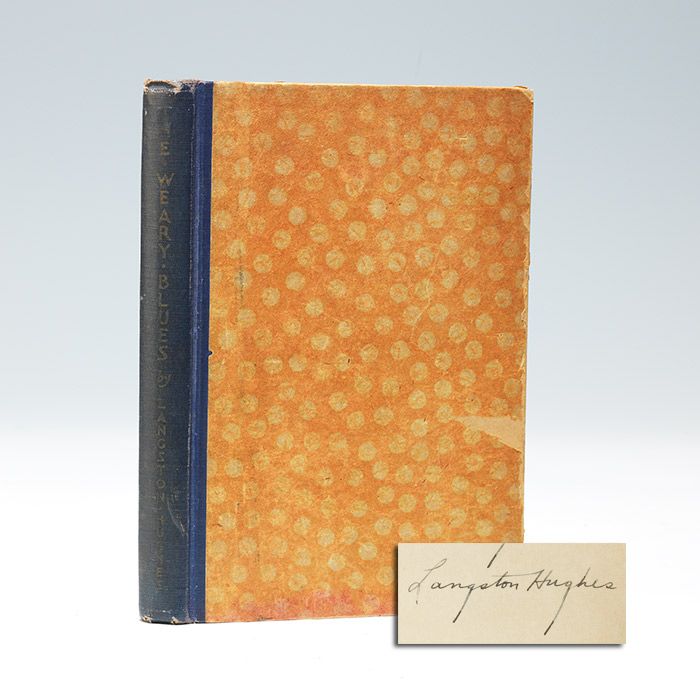

Not everyone was quite so comfortable with Locke???s rosy vision of the Harlem scene, though. While Locke aspired to a lofty ???spiritual Coming of Age” driven by intellectual elites, Langston Hughes focused on the world before him. He drew inspiration from jazz and the blues, and his poetry sought to capture the unvarnished moments of Harlem life that went unseen by the mostly white spectators of glittery ???uppercrust??? clubs.

His first collection of poetry, The Weary Blues, was a rousing success that won the 24-year-old numerous awards and the attention of a rapt audience well beyond Harlem. Its titular poem was the first to borrow form, tempo, and tone from the music it described, picked out on the piano by a melancholy man in a Lenox Avenue bar. (It was also intended to be read with musical accompaniment, as Hughes performed it with the Doug Parker Band in 1958.)

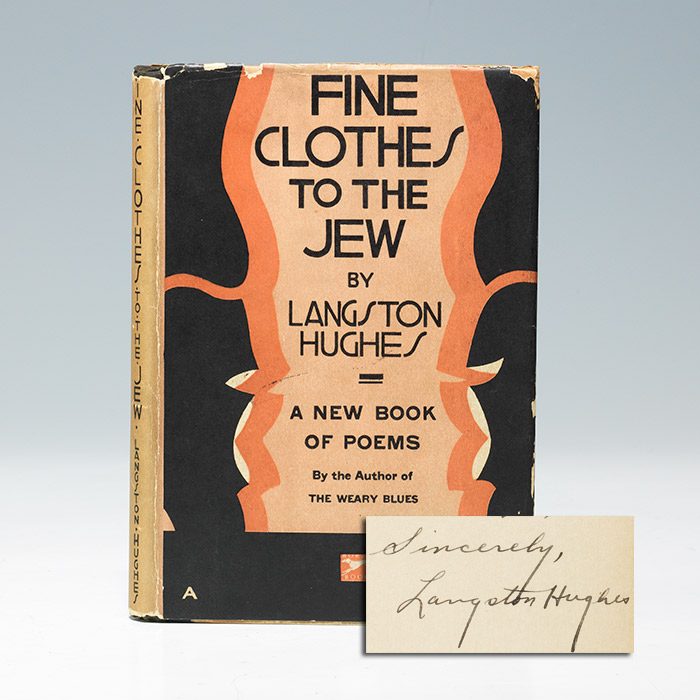

His next book went even further, and — to put it mildly — was not so well-received. Today, it???s considered one of Hughes??? most significant early achievements, but in its own day, Fine Clothes to the Jew immediately courted controversy, especially among African-American critics. They disliked its stark and unpoetic language, depictions of racism, use of crude dialect, and all-around provocative portrayal of Harlem life. This Harlem was a far cry from Locke???s world of cosmopolitan intellectual elites!

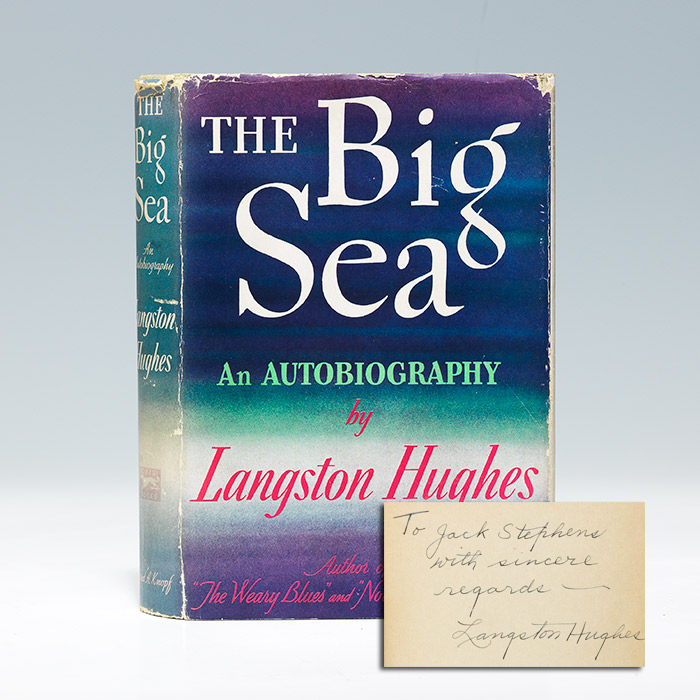

In his first autobiography, The Big Sea (one of the most detailed and fascinating “insider accounts” of the Harlem Renaissance ever written), Hughes acknowledged his critics??? concerns, but he remained resolutely dedicated to giving voice to the truths that he saw around him.

I personally knew very few people anywhere who were wholly beautiful and wholly good??? I knew only the people I had grown up with, and they weren???t people whose shoes were always shined, who had been to Harvard, or who had heard of Bach. But they seemed to me good people, too.

–Langston Hughes, The Big Sea, 1940.

There???s much (much, MUCH!) more to read from the Harlem Renaissance, but The New Negro and Langston Hughes??? poetry are inspiring starting points in an almost overwhelmingly rich web of creative projects. Take your reading copy to MoMA for the afternoon, and then visit our gallery around the corner to talk about next steps!