In this new series, I’ll highlight books that the Founding Fathers read, owned, wrote about, and were influenced by: works that were important in the creation of the United States of America.

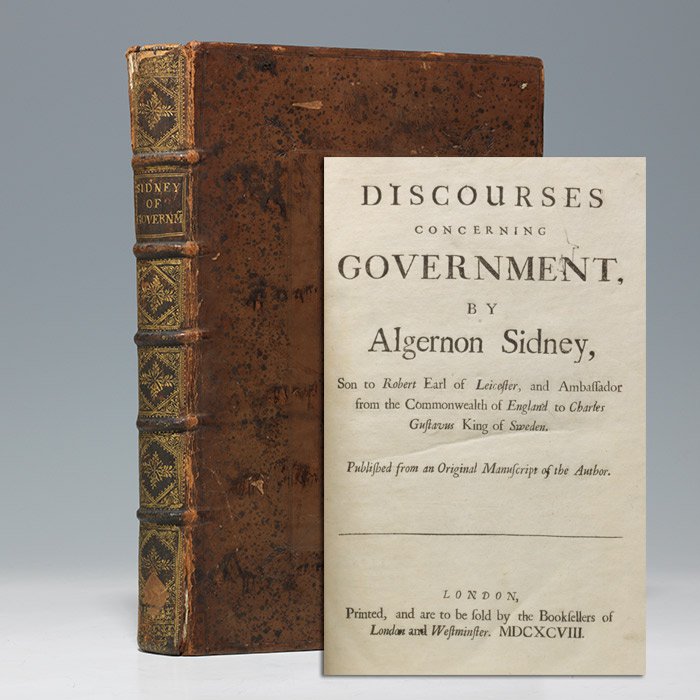

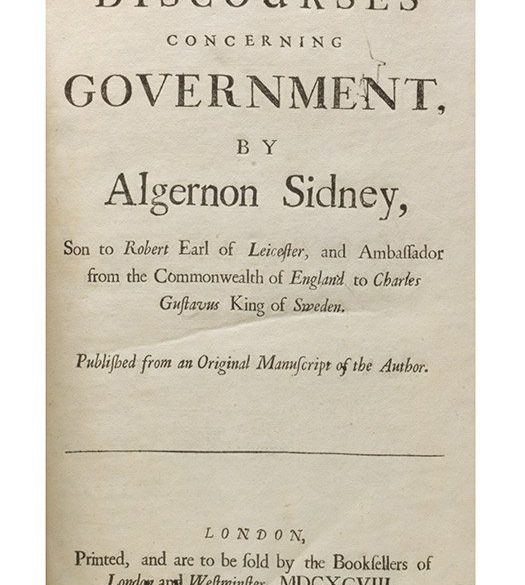

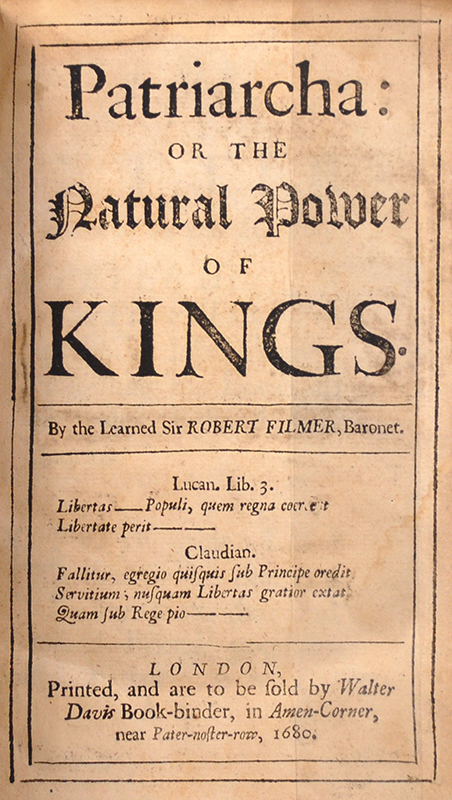

This first post is about Algernon Sidney’s Discourses Concerning Government, first published posthumously in 1698 and reprinted throughout the 18th century. Sidney’s famous defense of republican government was written in response to Sir Robert Filmer’s 1680 Patriarcha, which supported the divine right of kings to absolute power. (John Locke’s 1690 Two Treatises on Government was also written to refute Filmer.)

Sidney’s Discourses was owned in various editions by Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin. James Madison included it in his 1783 “list of books proper for the use of Congress.” Bernard Bailyn noted in The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution that Sidney was referred to “above all” by American revolutionary writers, and his Discourses “became, in Caroline Robbins” phrase, a “textbook of revolution” in America.

That which is not just, is not Law; and that which is not Law, ought not to be obeyed.

??? Sidney???s Discourses Concerning Government

Sidney, a political theorist and former member of Parliament, was executed for treason in 1683. Many leading Whigs were accused of involvement in the Rye House Plot against Charles II and his brother James, but Sidney???s trial and conviction were widely viewed as unjust. Two witnesses were needed to convict someone of treason, but there was only a single witness, so the prosecution used Sidney???s unpublished manuscript of Discourses as the second witness, and the judge famously ruled ???scribere est agere??????to write is to act.

David Hume described Sidney???s trial in his History of England and explained that his writings were ???favourable indeed to liberty??? but those principles have long been embraced by ???the best and most dutiful subjects.??? Hume declared that ???the evidence against him??? was not legal??? and called Sidney???s execution ???one of the greatest blemishes of the present reign.??? Parliament reversed Sidney???s conviction five years later, after the forced abdication of James II, and Discourses was published a decade after that.

???Throughout the eighteenth century Algernon Sidney was revered by radicals in Europe and America as a martyr to liberty,??? noted Alan Craig Houston in Algernon Sidney and the Republican Heritage in England and America. ???Perhaps nowhere was Sidney???s fame and influence more strongly felt than in revolutionary America.???

Benjamin Franklin paid tribute to Sidney in his Poor Richard Improved almanac for 1750 by writing under the month of December:

On the 7th of this Month, 1683, was the honourable Algernon Sidney, Esq; beheaded, charg???d with a pretended Plot, but whose chief Crime was the Writing an excellent Book, intituled, Discourses on Government. A Man of admirable Parts and great Integrity.

Thomas Jefferson cited Sidney???s Discourses as an important influence in writing the Declaration of Independence, and he recommended it be taught at the University of Virginia for ???the general principles of liberty and the rights of man in nature and in society.??? He praised the work in his correspondence, as in this 1804 letter:

The world has so long and so generally sounded the praises of [Sidney???s] Discourses on government, that it seems superfluous, and even presumptuous, for an individual to add his feeble breath to the gale. They are in truth a rich treasure of republican principles, supported by copious & cogent arguments, and adorned with the finest flowers of science. It is probably the best elementary book of the principles of government, as founded in natural right, which has ever been published in any language: and it is much to be desired in such a government as ours that it should be put into the hands of our youth as soon as their minds are sufficiently matured for that branch of study.

John Adams also praised the work in this 1823 letter to Jefferson:

I have lately undertaken to read Algernon Sidney on Government there is a great difference in reading a Book at four and twenty, and at Eighty Eight, as often as I have read it; and fumbled it over; it now excites fresh admiration, that this work has excited so little interest in the literary world???As splendid an Edition of it, as the art of printing can produce, as well as for the intrinsick merit of the work, as for the proof it brings of the bitter sufferings of the advocates of Liberty from that time to this, and to show the slow progress of Moral phylosophical political Illumination in the world ought to be now published in America.

You can see our 1698 first edition of Sidney???s Discourses Concerning Government on our website.

Comments

One Response to “Books the Founders Read: Sidney’s Discourses Concerning Government”

Jerry Yanoff says: April 4, 2015 at 1:17 am

Very interesting and well researched.