No artist, in the period before photography, traveled more widely among as many different tribes or made as many portraits and scenes of Indians from life.

–Robert J. Moore on George Catlin

In 1821, George Catlin left his law practice to pursue his passion: painting.

By 1829, George Catlin had failed as a painter.

After a few years of scraping by as a miniaturist—a form of painting considered tedious but economically feasible—Catlin attempted to take on the full-length portraits and history paintings of well-respected (and wealthy) artists. He had enjoyed some success through the patronage of New York Governor DeWitt Clinton, but boasting only the skills of a self-taught enthusiast, his luck did not last. (One fellow painter said of the artist and his portrait of Clinton: “He has the distinguished notoriety of having produced the worst full-length [portrait] which the city of New York possesses.”)

Catlin needed to find a way to distinguish himself from other artists…in a good way. He moved to Washington D.C. to find new markets, and hopefully establish some government commissions. One of his most important visits was to the celebrated portraitist Charles Bird King, who in a kind of fantastical coup had secured a longstanding contract with the government to paint the portraits of Native American visitors to the White House.

Through these portraits and the persistent collecting impulse of Superintendent of Indian Affairs Thomas McKenney, the War Department developed a sort of “Indian Museum” over the years that began to draw tourist traffic. Catlin visited this museum and later said it was an enormous inspiration.

But Catlin decided to take it one step further. Instead of waiting for Native Americans to visit D.C., Catlin would go to them.

…the history and customs of such a people, preserved by pictorial illustrations, are themes worthy the lifetime of one man, and nothing short of the loss of my life, shall prevent me from visiting their country, and becoming their historian.

In 1830 he headed to St. Louis with a letter of introduction to William Clark.

Yes, that William Clark, of the celebrated Lewis and Clark Expedition that had returned almost 25 years before. Clark was the commissioner of the newly formed Missouri Territory and thus probably the most powerful American west of the Mississippi. According to Catlin biographer Benita Eisler, Clark had also formed the first great collection of Native American artifacts in America.

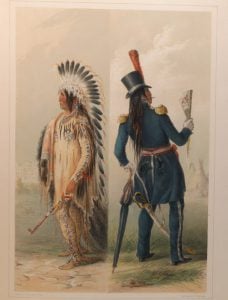

Clark took Catlin under his wing, allowing him to participate in and paint his meetings with Native American leaders. Perhaps most importantly, Clark arranged for Catlin to journey with members of the American Fur Trade up the Missouri to paint Native American tribes in their homelands.

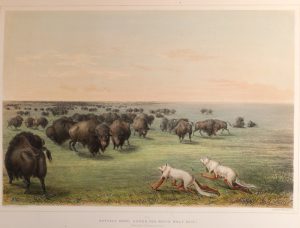

Between 1830 and 1836 Catlin took five trips into the “wilderness,” where he interacted with and painted Native Americans as a visitor and observer of their unique cultures.

For the most part Catlin was heartily welcomed, and in some cases, treated with awe. Called a “white medicine man,” many Native Americans viewed his ability to create likenesses as supernatural. Some feared the portraits, saying that a creation that looked so lifelike must have taken some of the life out of the source.

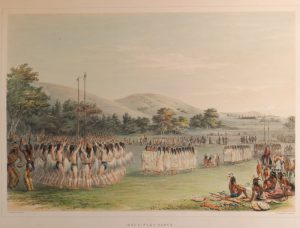

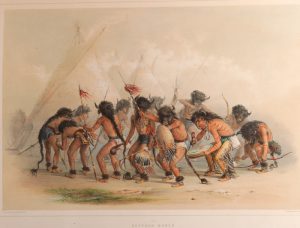

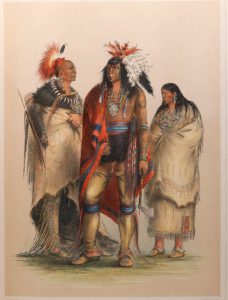

Catlin painted not only portraits of important figures, the subject of Charles Bird King and other artists based back East, but also scenes of everyday life and major cultural import. Perhaps most infamously, Catlin was the first American to document the Okipa ceremony of the Mandan tribe. Involving ritual torture of young men, this sacred religious ceremony seemed to contradict the Mandan’s famously peaceful and prosperous way of life. Four years after Catlin’s visit, the Mandans were almost entirely eradicated by a smallpox epidemic, leaving less than 150 survivors of the tribe.

After Catlin had completed five trips and hundreds of paintings, it was time to spread the word. Catlin began displaying his canvasses, along with Native American costumes, tools, and artifacts he had bartered or bought. The traveling show, called “Catlin’s Indian Gallery,” was often sprinkled with Catlin’s own descriptions of how each piece was painted or purchased. It can legitimately be called the first “Wild West Show.”

Frankly, as evidenced by his previous failures, Catlin was not the most talented artist. He was also certainly not immune to racist or imperialist inclinations, particularly by our 21st century standards. But he was the first to leave a visual record of many Native American tribes and their cultures, most of which were devastated or completely destroyed by the end of the 19th century. His value as an ethnographer, advocate, and yes, artist, for Native American tribes cannot be overstated.

Catlin’s hopes of selling his gallery to the government were dashed by a combination of timing (hello Jacksonian era) and politics: Catlin was a major voice of dissent against the continually horrific treatment of Native American tribes. For this perhaps we can be grateful, because without this failure Catlin may not have decided to produce the lavishly illustrated books that have spread his record and his message far beyond the 1830s urban visitors to his Indian Gallery. His 1844 North American Indian Portfolio, a large folio production with 25 hand-colored lithographic plates, ranks as one of the most magnificent 19th-century works on the American West, and on the peoples native to it.

Comments

2 Responses to “An Artist Finds His Calling: The Story of George Catlin, the “First Artist of the West””

Matthew Alexander says: September 17, 2013 at 2:27 am

Some of Catlin’s lithographs are currently on show at The Museum of Manchester, U.K. http://t.co/zSwvf8UnGs is a link to a picture of hand drawings on stock paper made by Native Americans around the time Catlin carried out the works shown above.

Matthew Alexander says: September 17, 2013 at 10:35 am

And here is the museum’s link for those interested: http://www.museum.manchester.ac.uk/whatson/exhibitions/warriorsoftheplains/