My countrymen??? will come reluctantly into the idea of independency, but time and persecution brings many wonderful things to pass; and by private letters which I have lately received from Virginia, I find that ???Common Sense??? is working a powerful change there in the minds of many men.

??? George Washington letter to Joseph Reed, April 1, 1776

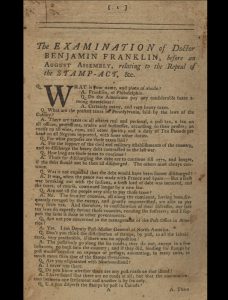

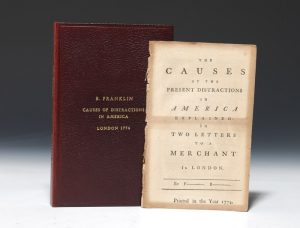

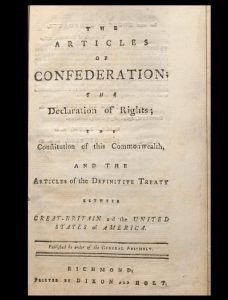

Many of the most important, influential, and popular writings of the American Revolution were printed as pamphlets. Bernard Bailyn, in The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, noted that pamphlets were ???highly flexible, easy to manufacture, and cheap??? and were printed ???wherever there were printing presses, intellectual ambitions, and political concerns.???

It was in this form??? that ???the best thought of the day expressed itself???; it was in this form that ???the solid framework of constitutional thought??? was developed; it was in this form that ???the basic elements of American political thought of the Revolutionary period appeared first?????? Explanatory as well as declarative, and expressive of the beliefs, attitudes, and motivations as well as of the professed goals of those who led and supported the Revolution, the pamphlets are the distinctive literature of the Revolution. They reveal, more clearly than any other single group of documents, the contemporary meaning of that transforming event.

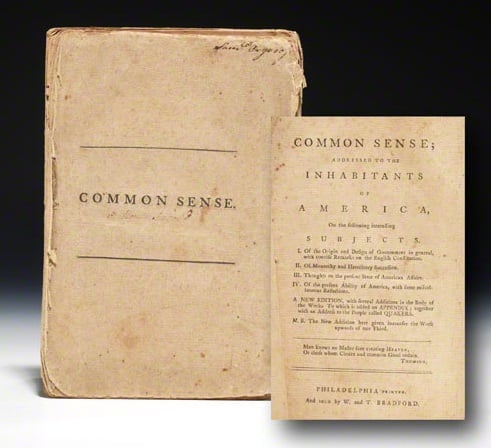

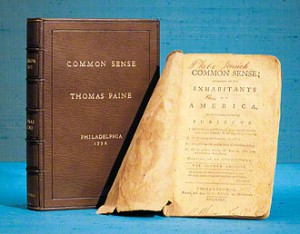

A typical pamphlet was under fifty pages and made of folded printed sheets sewn together with or without paper wrappers. Pamphlets still in the form in which they were issued are particularly scarce, as those that were kept were often rebound or bound together with other pamphlets to form a sammelband.

Many pamphlets were printed in a single edition of only a few hundred copies. Though some popular works may have had print runs closer to a thousand, it was common for printers to produce small printings and go back to press as needed to meet demand. This was because paper was expensive and had to be purchased in advance???small printings required less capital and risk. Paper shortages during the Revolutionary War also kept printings small.

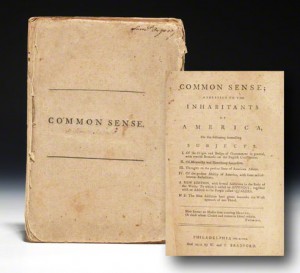

Bailyn estimated that more than 400 pamphlets on the American-British controversy were published between 1750 and 1776, and by 1783 over 1500 had appeared. By far the most famous and best-selling pamphlet of the American Revolution was Common Sense, written by Thomas Paine but published anonymously.

The first edition of Common Sense was published in Philadelphia by Robert Bell and advertised for sale on January 9, 1776. It sold out within a week. Paine planned to give his share of the profits to the American troops, but when Bell told him there were no profits, Paine dismissed him and hired William and Thomas Bradford to publish a new enlarged edition at a lower price. Bell published an unauthorized second edition, advertised on January 27th.

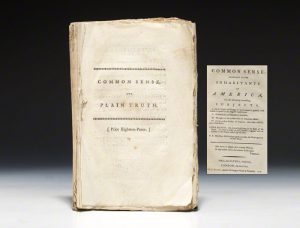

Bradford???s edition (with Paine???s additions, which increased the text by more than a third) was advertised on February 14th. Bell pirated Paine???s new material and published it in Large Additions to Common Sense, and he continued to publish unauthorized editions of Common Sense.

Copies of the Bell and Bradford editions were carried and mailed throughout the colonies, and new editions were printed in a dozen other cities over the following weeks and months. The publication dates of some editions can be estimated from newspaper advertisements. Editions printed in cities closer to Philadelphia were generally earlier than those farther away, as were those printed in major cities rather than smaller towns. Another clue to timing is which Philadelphia edition the text is based on whether it includes Paine???s additions. The first New York edition, a reprint of Bell???s first edition, was advertised on February 15th and is believed to be the first printed outside of Philadelphia. The Boston edition was advertised on April 8th.

It is estimated that Bell printed about 1000 copies of the first edition and at least that many of his second edition. The Bradfords hired two local printers to each produce about 3000 copies of the expanded edition. The print runs of other American editions are unknown but were likely much smaller, as Philadelphia was the largest city in America with a population double that of Boston. Only six colonies produced pamphlet printings in 1776???Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and South Carolina.

The 1776 London editions drew many Englishmen to support the American cause, though publishers deleted material critical of the king to avoid prosecution. Trevelyan noted that

Common Sense turned thousands to independence who before could not endure the thought. It worked nothing short of miracles.

Despite the extraordinary popularity and influence of Common Sense, relatively few copies of these 1776 editions survive, as they were passed around and read to pieces, thrown away, or lost in the chaos of the Revolution. They are among the most desirable works in Americana collecting, and though a number of the surviving copies are in institutions, over the years Bauman Rare Books has offered copies of the Bell and Bradford Philadelphia editions as well as copies printed in New York, Boston, Providence, London, and other cities.

Pamphlets like these were the soul of the American Revolution???in the words of Jefferson, ???the expression of the American mind.???