“HAVE YOU ANY THOUGHTS ON THIS POINT?”: FIVE REMARKABLE LETTERS IN A UNIQUE 1929 CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN FELIX FRANKFURTER AND COLLEAGUE MAX LOWENTHAL OF THE WICKERSHAM COMMISSION, A RARE GLIMPSE INTO THE CLOSE FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN TWO INFLUENTIAL MEN AT A TURNING POINT IN THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN CRIMINOLOGY

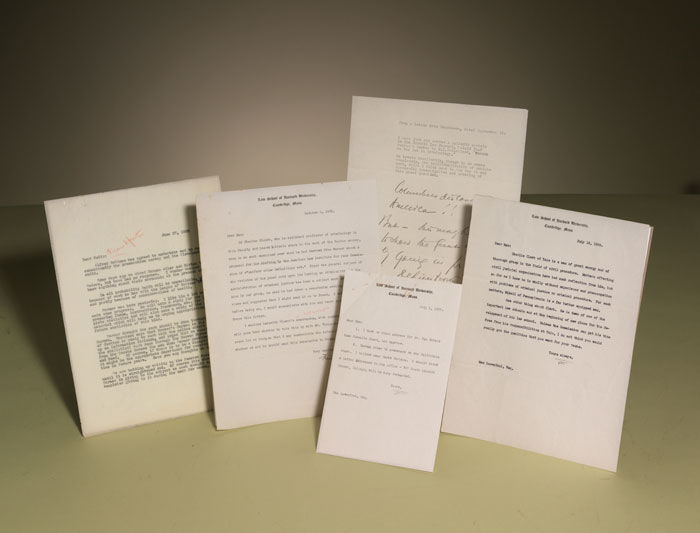

FRANKFURTER, Felix. Typed letters signed. WITH: Autograph note signed. Cambridge, Massachusetts, circa 1929. Five single sheets each typewritten on recto: two on printed letterhead measuring 8 by 10-1/2 inches; two on plain sheets measuring 8 by 10-1/2 inches with one typewritten and completed in manuscript; one on printed letterhead measuring 5 by 8 inches. $2500.

A unique collection of original letters in a correspondence between Felix Frankfurter, future Supreme Court Justice, and Max Lowenthal, then secretary of the landmark Wickersham Commission, five items altogether, containing three typewritten letters signed by Felix Frankfurter, along with one autograph note signed by him, and a typed letter addressed to him by Lowenthal, later a key figure in the Truman administration, each speaking to the close friendship between these men and their shared goal of producing the first federal study of American law enforcement.

“The most controversial Supreme Court justice of his time,” Felix Frankfurter (1882-1965) taught at Harvard Law School from 1913-39. It was during this tenure that “he became the friend and tutor of two generations of government servants… inculcating in students a love of the law and of service to government.” Among those profoundly influenced by Frankfurter’s emphasis on public service was Harvard lawyer Max Lowenthal (1888-1971), who became a close colleague and after volunteering his pro-bono services in 1929 as secretary of the newly formed Wickersham Commission, often relied on Frankfurter’s advice on how to achieve its goal of solving a crisis in Prohibition enforcement and the larger task of producing the first federal study of American law enforcement systems. A precursor to the 1960s President’s Crime Commission and itself modeled on a 1922 Cleveland survey codirected by Frankfurter and Roscoe Pound (who served on the Commission), this two-year coalition of experts ultimately published a series of landmark reports from 1930-31, fundamentally altering America’s approach to judicial and police conduct, penal and parole systems, juvenile crime, and the impact of race and poverty. This collection of letters provides rare insight into the work of that Commission and into a friendship “cemented with ideas”-one that united these two men who were dedicated the belief that “intellect could solve practical problems and make the world a fairer place” (Hall, 314-15)

The first of these letters, dated June 27, 1929, is the unsigned carbon of a typewritten letter from Lowenthal to Frankfurter, reading “Dear Felix: [followed by “Frankfurter” handwritten in red] // Alfred Bettman has agreed to undertake and to run concurrently the prosecution survey and the Cleveland audit. // Some days ago we wired Herman Adler and Miriam Van Waters, but have had no response. I wonder whether you know anything about their movements at the present time. // In all probability Smith will be unavailable, partly because of work he has with the League of Nations [“and”-handwritten above line in blue ink] at college, and partly because of preparing forms, instructions, framework, etc. for future complete statistics of this kind. // Warner thought the work should be done through the Census Bureau. Harrison says that Hoover’s Bureau in the Department of Justice is ready to work with the police chiefs and to set up an information division, and urges that we consider having the statistical work done through the Hoover Bureau, transferring from the Census Bureau the men whom Warner mention—Truesdell and Mead. Of course, if there is to be a Ministry of Justice it might be the appropriate department for receiving these statistics in future years. Have you any thoughts on this point? // We are holding up writing to the Pension Bureau people until it is straightened out. Of course this should not delay Warner in giving to the subject as much thought as he has contemplated giving to it during the next few weeks.” Of those cited here, Alfred Bettman wrote the Commission’s Report on Prosecution (1931); Doctor Herman Adler was a Harvard trained psychiatrist; Dr. Miriam Van Water, authored the Commission’s highly influential report The Child Offender in the Federal System of Justice (1931); Sam Bass Warner wrote its Survey of Criminal Statistics in the United States (1931). The further identities of Smith, Harrison, Truesdell and Mead remain undetermined. The next in this collection appears to be Frankfurter’s response to Lowenthal’s attempts, following that letter, to contact Dr. Adler and Dr. Van Waters. Typewritten on a sheet of Harvard Law School letterhead that measures 5 by 8 inches, this is dated “July 1, 1929” and reads, “Dear Max: // 1. I know no other address for Dr. Van Waters than Juvenile Court, Los Angeles. // 2. Herman Adler is somewhere on the California coast. I believe near Santa Barbara. I should think a letter address to his office—907 South Lincoln Street, Chicago, will be duly forwarded. // Yours, [signed] FF. // Max Lowenthal, Esq.”

The third letter in this series, typewritten on an 8 by 10-1/2 inch sheet of Harvard Law School letterhead, is dated “July 18, 1929” and reads, “Dear Max: // Charlie Clark of Yale is a man of great energy and of thorough grasp in the field of civil procedure. Matters affecting civil judicial organization have had much reflection from him, but so far as I know he is wholly without experience and preoccupation with problems of criminal justice or criminal procedure. For such matters, Mikell of Pennsylvania is a far better equipped man. // One other thing about Clark. He is dean of one of the important law schools and at the beginning of new plans for the development of his law school. Unless the Commission can get his time free from his responsibilities at Yale, I do not think you would really get the qualities that you want for your tasks. // Yours always, [signed] FF. // Max Lowenthal, Esq.” As indicated here by Frankfurter, Charles Clark was then Dean of Yale Law School and William Ephraim Mikell was Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School. The fourth item in this series is an undated autograph letter on a single sheet measuring 8 by 10-1/2 inches. It is typewritten, then completed in six manuscript lines. The first section is typewritten and reads, “From a letter from Hutcheson, dated September 18: // I have just run across a splendid article in the Cornell Law Journal, Vol. 14 No. 2 February number by E.H. Sutherland, “Person vs. The Act in Criminology.” // He treats excellently, though by no means completely, the individualization of punishment, which I think must be the key to any successful investigation and ordering of this great question.” This is followed by a section handwritten in pencil that comments, “Columbus discovered America!! // But—this maybe used to show the great damages of [illegible word] in [illegible word] Definitions of [illegible word].” The letter’s reference to “Hutcheson” most likely speaks to an earlier letter received from Joseph Chappell Hutcheson, Jr., a federal judge who served as adviser on the Wickersham Commission. The recipient of Frankfurter’s is unnamed but is, in all likelihood, Max Lowenthal.

The final letter in this collection, dated “October 9, 1929,” is also typewritten on an 8 by 10-1/2 sheet of Harvard Law School letterhead. It reads, “Dear Max: // Dr. Sheldon Glueck, who is assistant professor of criminology in this faculty and has an intimate share in the work of the Boston survey [sic], came to me much exercised over what he had learned from Warner about a proposal for the drafting by the American Law Institute for your Commission of a ‘uniform crime definitions act.’ Since the general subject of the revision of the penal code upon its bearing on criminality and the administration of criminal justice has been a subject much under discussion by our group, he said he had drawn a memorandum setting forth his views and suggested that I might send it on to Pound. I told him that before doing so, I would communicate with you and learn your wishes. Hence this letter. // I enclose herewith Glueck’s [“-not sent to file” handwritten in red] memorandum, with supporting data. You will know best whether to take this up with Mr. Wickersham. But in any event let me know, so that I may communicate the information to Glueck, whether or not he should send this memorandum to Pound. // Very cordially, [signed] Felix Frankfurter.” Harvard lawyer Sheldon Glueck, who was instrumental in emphasizing the use of scientific models and research in criminology, was, as is mentioned here, assistant to Frankfurter in his 1926 Harvard Crime Study. Later Dr. Glueck was one of the first to publish a study of war crimes’ prosecution after serving as U.S. adviser in the Nuremberg Trials.

An exceptional correspondence in about-fine condition.