“A FINAL TESTAMENT TO THE HUMAN VALUES HE CHERISHED MOST”: GEORGE WASHINGTON’S LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT, INCLUDING THE EMANCIPATION OF HIS SLAVES

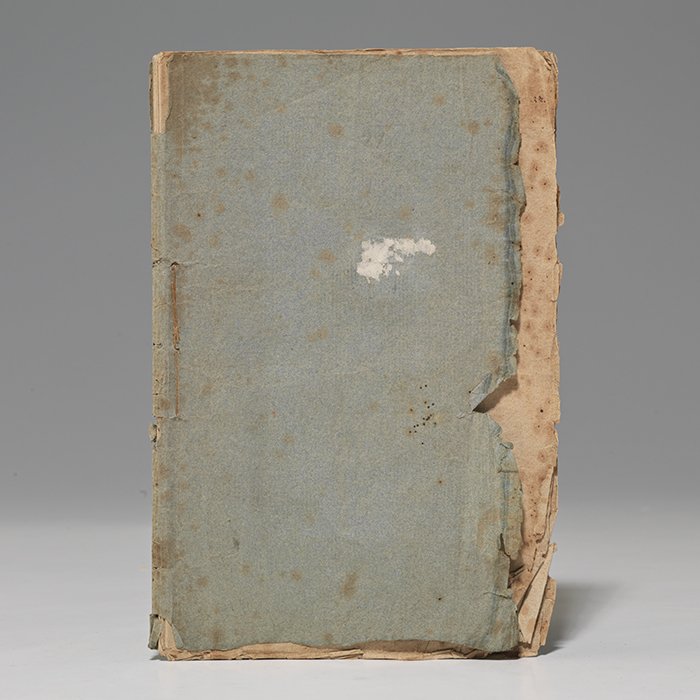

WASHINGTON, George. The Last Will and Testament of Gen. George Washington. Boston: John Russell and Manning & Loring, 1800. Small octavo, original blue paper wrappers, stab-sewn as issued; pp. 24. $9800.

Early edition, issued the same year as the Alexandria first edition, of Washington’s will, "one of the most historically significant and personally revealing documents he ever wrote." Rare in original wrappers.

With this will, George Washington "accomplished something more glorious than any battlefield victory as a general or legislative act as a president. He did what no founding father dared to do, though all proclaimed a theoretical revulsion at slavery. He brought the American experience that much closer to the ideals of the American Revolution and brought his own behavior in line with his troubled conscience" (Chernow, 802). This remains "one of the most historically significant and personally revealing documents he ever wrote… his final instruction concerned [his personal servant] Billy Lee, who had been hobbling around Mount Vernon for over a decade on two badly damaged knees. He should be freed outright upon Washington's death and provided with a small annuity along with room and board, 'as a testimony to my sense of his attachment to me, and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War.' There it was, a clear statement of his personal rejection of slavery… He was, in fact, the only politically prominent member of the Virginia dynasty to act on Jefferson's famous words in the Declaration of Independence by freeing his slaves. He had been brooding about how to do it for over five years, procrastinating within a tangle of financial factors, and the drafting of his will represented his ultimate recognition that the only way to do it was, well, to do it. Though conscience, his deep moral revulsion at the blatant wrongness of human bondage, surely played an important role in his decision, his motives were not purely or merely moral, as they seldom were. For he knew that posterity was watching, and that his statement on this score would help to clear his legacy of the major impediment to his secular immortality" (Ellis, 261-4).

"In another visionary section of the will, Washington left money to advance the founding of a university in the District of Columbia" (Chernow, 803). In addition, "the principle he chose to apply in distributing the fortune he had accumulated represented a personal statement almost as dramatic as his decision to free his slaves: there would be an equal division among 23 heirs… Washington clearly wanted to live on in the memory of succeeding generations as the founding father of an emerging American empire, but the terms of his will assured that he would not live on as the founding father of a prominent American family… none of his heirs received more than a modest nest egg… All in all, when Washington signed his will on July 9, 1799, he was doing more than putting his financial affairs in order. The will was also intended as a final testament to the human values he cherished most. He had time and time again shown himself to be an aficionado of exits, whether it was the theatrical performance before the officers of the Continental army at Newburgh, surrendering his sword at Annapolis, or the stately cadences of the Farewell Address… his will was his ultimate exit statement, a wholly personal expression of his willingness to surrender power in a truly final fashion as he prepared to depart the stage of life itself" (Ellis, 264-5). In addition to his home in Alexandria, Washington bequeaths to his wife Martha "my Household and Kitchen Furniture, of every sort and kind, with the Liquors and Groceries which may be on hand at the time of my decease." To the Earl of Buchan, he bequeaths "the Box made of the Oak that sheltered the great Sir William Wallace, after the Battle of Falkirk"; to his brother Charles, "the gold-headed Cane left me by Dr. Franklin"; and to General LaFayette "a pair of finely wrought Steel Pistols, taken from the enemy in the Revolutionary War." Washington died on December 14, 1799. First published in Alexandria earlier in 1800. Sabin 101754. Howes W145. Evans 39000.

Original wrappers worn but intact, with closed tear to rear cover; moderate foxing to interior, very good. Scarce and desirable in original wrappers.