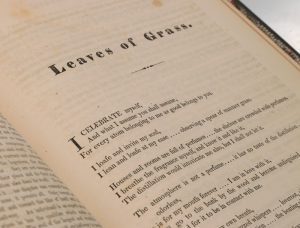

One of the world’s most important books of poetry may never have been published if the poet had not been a printer himself. I speak of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, perhaps the most influential book of poetry to be composed by an American.

Like his contemporary Mark Twain, Walt Whitman first learned to write by working at a printer’s shop. Whitman’s father pulled him out of school at age eleven to help support the family, and by twelve years of age Whitman was working as a printer’s devil—a sort of young apprentice assigned menial tasks around the shop. For literally decades before Whitman’s first edition of Leaves of Grass was published, he produced editorial content, short stories and poems for various newspapers where he also served as a printer.

Although we can’t be sure, it appears that Whitman couldn’t find a willing publisher for his little book of organic, American poems. Scholars say this because when Whitman did publish the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855, he not only paid all the expenses, but also asked a printer friend who had probably never actually published a book before.

Andrew Rome’s press was not equipped to handle books at all—it specialized in legal documents.

The main tell is the paper size. Poetry books in the 19th century tended to be printed in little pocket-sized volumes, befitting the trend of portable books perfect for a long stroll along the lake—the Wordsworthian culture of walks among the daffodils. Whitman’s first edition Leaves of Grass, however, measures 8 1/8” x 11 1/8”. This book does not fit in one’s pocket. It does, however, approximately match the size used for legal documents by the Rome press.

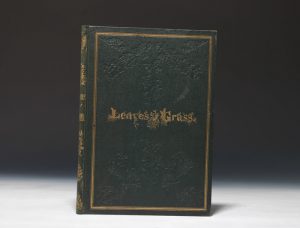

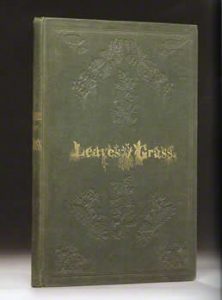

The volume is tall and slender. It is extremely fragile. But, oh, it was a work of love. Whitman designed the cover as well. His title grows roots and leaves, set into a lush green cloth that evokes lying on the grass on a summer evening. The design of the book was an ars poetica in itself: a declaration of a different type of poetry, rooted in the leaves and the soil of American experience.

Only 795 copies of the first edition were printed. Whitman, bankrolling the project himself, realized after about 300 copies that he didn’t have the funds to keep producing the book exactly how he wanted it. Soon he had removed the gilt edges and some of the gilt stamping, and by the end he discarded the cloth binding entirely in favor of paper covers.

A recent census estimates that only about 200 copies survive.

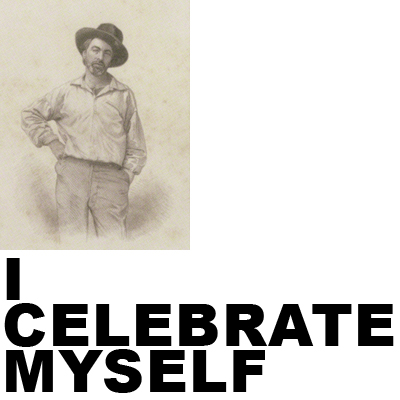

Like a number of other revolutionary books, this first edition does not name the author on the title page. Whitman, so proud of his body and bearing, couldn’t resist a frontispiece portrait: the iconic image of him, hand placed saucily on his hip, with working clothes and hat.

Like his poetry, his book design, the portrait and the title page all speak to the same message:

I celebrate myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease…observing a spear of summer grass.

Comments

8 Responses to “The Story: Walt Whitman’s First Edition Leaves of Grass”

Jay Kostel says: July 2, 2013 at 1:51 am

I met you at the store today, asked you about books my friend found. Thanks you were very kind and insightful!

Rebecca Romney says: July 3, 2013 at 9:43 pm

Glad to help!

Rich Scary says: July 2, 2013 at 9:38 am

One of the great advantages of the internet and social media is the ability to self publish. Let’s face it, most of us don’t have our own print shops and unfortunately, there are relatively few literary agents and publishers out there. It is very hard for an unknown writer to get their work published.

With self-publishing, print-on-demand and ebooks, aspiring writers have more outlets then ever and will find it easier and fairly inexpensive to walk in the footsteps of Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, Edgar Allen-Poe, Tom Clancy and countless other famous writers who had to take a chance on themselves before the world realized how brilliant they were.

Rebecca Romney says: July 3, 2013 at 9:42 pm

This is a great point. Although one aspect about printers-turned-writers is how they would conceive of their work based on how it would look on the page. Whitman did this, as well as Virginia Woolf. I wonder if in the future that will be more the trait of graphic-designers-turned writers?

matt Howard says: July 17, 2013 at 2:00 pm

Very informative about all aspects of rare book collecting thanks Matt Howard.

Lawrence Stanfield says: July 31, 2013 at 3:42 pm

Very interesting and well written. This information is something that every teacher should use in introducing students to Whitman and sadly is often neglected. It really brings the poet into a sphere of reality with which the student can identify.

Rebecca Romney says: August 1, 2013 at 5:35 pm

Thank you. I agree–there are many ways to bring literature to life, and often stories from behind the scenes can make it feel more identifiable. We often have teachers take home our catalogues to show students images of first editions, so they can see what the original editions look like.

Brian Ebersole says: May 31, 2015 at 5:00 pm

I live near where Whitman wrote parts of Leaves of Grass. It makes me wonder if the last sentence was inspired by his summer home in Laurel Springs NJ. Writing pages of it at Silver Spring just a short walk away. I posted a picture of the spring on Rebecca’s twitter page around Easter. So awesome to see that history, then read it.

Thanks for the insight.