When it comes to polar explorers, the first thing to know is that they were all maniacs.

The second thing to know is that they were all maniacs.

Not exactly an objective observation, I know, but consider this: many of the voyages I’ll be chronicling in the weeks to come ended in unqualified disaster.

The kind of disaster that sees your ship trapped in the ice for months or even years (as happened to both John Ross and Ernest Shackleton). The kind of disaster that reduces you to eating boot leather and lichen (as happened to John Franklin), or wandering out into a blizzard because freezing to death in your tent is taking too long (as happened to a member of Robert Scott’s final expedition). These are the kinds of disasters that they write songs about.

There’s a mystique, a romanticism attached to polar explorers. Indeed, what kind of person must you be in order to sail, literally, into the unknown? How rampant your curiosity, how huge your ego, how deep your fortitude?

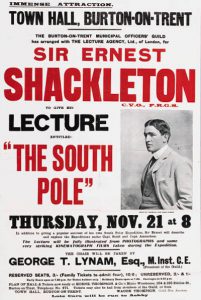

So, first on the docket: Ernest Shackleton.

Not too long ago, a few colleagues and I made a game of assigning high school archetypes (Breakfast Club-style) to the luminaries of polar exploration. Shackleton was universally acknowledged as Mr. Popularity – starting quarterback and class president all rolled into one.

Born in 1874 to a large Anglo-Irish family, Shackleton left school at 16 and went to sea. He spent the better part of the next decade sailing to the far corners, performing myriad duties, and climbing the ranks. In 1898, he achieved the professional status of Master Mariner, which meant he was qualified to command a British ship anywhere in the world. Alas, he wouldn’t see his own command until 1907.

(Bonus fact: Circa 1907, Ernest’s older brother, Francis, was accused of looting the Irish Crown Jewels. He was eventually cleared but later jailed for passing stolen checks.)

In 1901, Shackleton was appointed – as a result of some savvy networking – to Captain Robert F. Scott’s British National Antarctic Expedition (1901-1904), which is more simply called the Discovery expedition (after its ship). Shackleton’s duties aboard Discovery included seawater analysis, ward-room catering, and maintenance of stores and provisions, as well as arrangement of “the entertainments.” Too, he edited the expedition’s magazine, The South Polar Times.

Limited first edition of the complete run of South Polar Times.

Smith & Elder, 1907 & 1914. Volume I edited by E. Shackleton,

issued in an edition of only 250 copies.

Shackleton was apparently the most popular of the officers, but unfortunately, he became terribly ill during Scott’s primary southern sledge journey and was sent home aboard a relief supply ship in 1903.

The years following his return perpetrated a series of highs and lows. In 1904, Shackleton became Secretary for the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, and it was around this time that he began to formulate a plan for his return to the Antarctic. Finally, in early 1907, Shackleton presented his plan for the British Antarctic Expedition, which would go on to be immortalized as the Nimrod expedition (1907-1909).

(Bonus fact: One of the investors in the Nimrod expedition was the 1st Earl of Iveagh, Edward Guinness. Yes, that Guinness.)

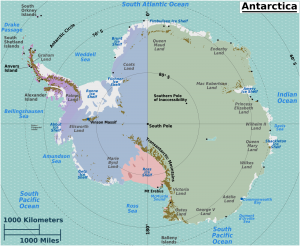

Nimrod’s primary goals were to achieve both the geographical South Pole and the South Magnetic Pole, as well as to pursue a steady compliment of scientific explorations. But before they could attempt anything, they had to traverse thousands of nautical miles.

(Bonus fact: Before the Nimrod left England, Robert Scott extracted a promise from his former officer that Shackleton would avoid certain latitudes, primarily the McMurdo Sound. Scott had earmarked that area for his own future – though at the time unannounced – expedition. While Shackleton initially agreed, he was ultimately forced to land in that very Sound in order to secure safe anchorage. )

It took Nimrod the better part of four months (early August to late November 1907) to reach Lyttelton, New Zealand. After spending several weeks gathering additional supplies and crew, they cast off again on New Year’s Day 1908. They sailed for two weeks before reaching the Barrier (now referred to as the Ross Ice Shelf), another week to find safe anchorage in McMurdo Sound, and three weeks beyond that to establish their base camp. Over the course of the next year, the fickle and unpredictable nature of both the weather and the ice meant that the crew’s plans and goals often had to shift quickly and unexpectedly. Nevertheless, their accomplishments continue to amaze even today.

They were the first to summit Mt. Erebus (a 12,500-foot active volcano). They were the first to reach the approximate location of the South Magnetic Pole, which (in case you didn’t know) is a moving target. They discovered (and named) the Beardmore Glacier. They were the first to cross parts of the Polar Plateau. They accrued myriad points of scientific data relating to topography, geology, meteorology, and more. And although they didn’t achieve the geological Pole, they did come within 100 miles – closer than anyone else had ever managed. These feats, however, didn’t come without cost.

While the crew prepared to land supplies, Aeneas Mackintosh (second officer) lost his right eye after being accidentally struck with a wayward hook-and-tackle. While summiting Erebus, Phillip Brocklehurst (assistant geologist) developed frostbite severe enough to see toes amputated. Jameson Adams (meteorologist) had his leg sheared to the bone after being kicked by a pony. Eric Marshall (surgeon and cartographer) contracted a severe case of dysentery. Nearly everyone fell down a crevasse at some point. Nearly everyone flirted intimately with starvation. Snow-blindness was common. A majority of the ponies were shot for food , while others died after eating too much volcanic ash.

(Bonus fact: Emily Shackleton once revealed that the only thing her husband said about not achieving the Pole was “I thought you’d rather have a live donkey than a dead lion[.]”)

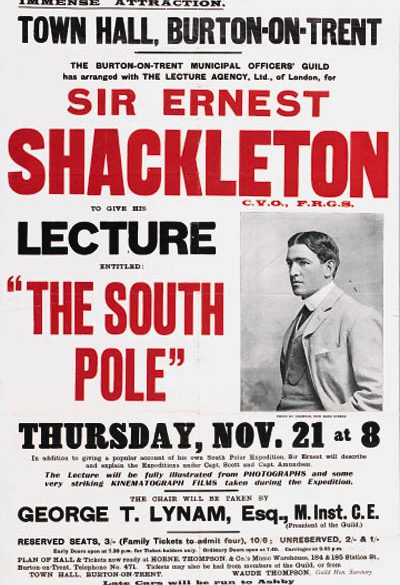

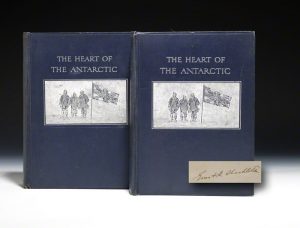

Shackleton and his crew received a hero’s welcome upon their return to England, and Shackleton would go on to detail the expedition in both lecture tours and in his book, Heart of the Antarctic, which remains a cornerstone in any Polar collection.

(Bonus fact: In 2010, several cases of Scotch whisky and brandy were uncovered by a team from the Antarctic Heritage Trust. Turns out they were left/forgotten there by our man, Ernest. By reverse-engineering one of the bottles, the master brewers at Whyte & Mackay – who supplied the crates of Mackinlay’s “Rare and Old” whisky for Shackleton – have since been able to recover the scotch’s formula, which was lost in the intervening years.)

Read Part II here, where disaster abounds during the Endurance expedition (1914-1917).

Comments

2 Responses to “Ernest Shackleton: Mr. Popularity (Part I)”

Matt howard says: October 13, 2013 at 8:54 pm

Your knowledge is inspiring when I read reviews not many are true to subject there prepaired From book they read hours before. Yours is because you love to express your knowledge of something you know no need to brush up text for text it’s shows I have same bug about Dickens I think maybe I am becoming an Antiqurian as I sell every and anything to get more Dickens rare 1st editions and my life will be compleat only when that little red book with 3/4 1st 1st comes out of hiding I have 1st 2nd 1st 3rd 1st 4th but that 1st 1st battle of life will be my crowning moment in life keep the good work up Matt Howard.

Embry Clark says: October 30, 2013 at 11:56 pm

Thanks, Matt! I’m glad you enjoyed reading about Shackleton. I find these guys pretty fascinating. Be sure to watch for Part II, which will be posted this week. And good luck on your Dickens collection!