When we left off last, Ernest Shackleton had just returned to England in the wake of his Nimrod expedition (1907-1909). He was hailed as a hero and showered in attendant praise – a gold medal from the Royal Geographical Society, congratulatory letters from other famed polar explorers, and even a knighthood from the King. His subsequent lecture tour and written account (Heart of the Antarctic) were both hugely successful.

(Bonus fact: In addition to the accolades, Shackleton also returned from Antarctica deeply in debt. In order to cover the most pressing of those debts, he was ultimately awarded a £20,000 grant from the British government. In today’s pounds, that rounds up to about £1.7 million.)

In an attempt to cash in on his newfound celebrity, Shackleton invested in a number of business enterprises – a tobacco company, a series of collectors’ stamps, even a Hungarian mine – but alas, each one failed. By 1910, he turned his attentions to the possibilities of a return trip to Antarctica, which he referred to simply as “going South.”

By then, however, much depended on the success or failure of the British Antarctic Expedition, led by Captain Robert Scott aboard the Terra Nova. In June 1910, Scott set out yet again to reach the South Pole – this time in a race against Norway’s Roald Amundsen. (More on these two in weeks to come.)

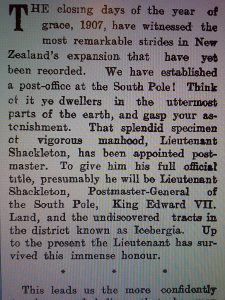

(Bonus fact: At the end of 1907, just prior to departing New Zealand aboard the Nimrod, Shackleton was appointed as a NZ Postmaster and afforded more than 20,000 NZ “Penny Universal” stamps to be used on the expedition.)

Because he assumed that either Scott or Amundsen would at last achieve the Pole, Shackleton set his sights on the final “great main object of Antarctic journeyings” – a sea to sea transcontinental crossing. And thus, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914-1917) was first announced in December 1913 and underway by August 1914. It would go on to be immortalized as the Endurance expedition (after its primary ship).

(Bonus fact: The first proposal for a transcontinental Antarctic crossing actually came from a Scotsman, William Speirs Bruce, in March 1910. Bruce was ultimately done in by a lack of funding but later gave his blessing to the Endurance expedition.)

The expedition consisted of two ships (the Endurance and the Aurora) and two crews (56 men in all). The Endurance launched from Plymouth in early August 1914. They reached South Georgia (via a brief stopover in Buenos Aires) by late October. After spending several weeks gathering additional supplies and crew, they once again set sail in early December.

(Bonus fact: The Endurance left England just as World War I was breaking out. While Shackleton initially contacted the Admiralty in order to offer his ships, crew, and stores in service of the country, he was instructed to proceed by First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. At the time, few suspected just how long and how devastating the Great War would become.)

From South Georgia, Shackleton set course for Vahsel Bay in the Weddell Sea. It was his intent that once they’d landed, he and six other men would form the Transcontinental Party. The ship’s remaining crew would then split into smaller groups, each of which would pursue its own course of scientific work. The Aurora meanwhile launched from Tasmania on Christmas Eve 1914. Per Shackleton’s instructions, the ship set course for McMurdo Sound in the Ross Sea, where the crew would then lay-in supply depots along the Ross Ice Shelf, which the Transcontinental Party would use as they made their way from the Pole toward the Ross Sea.

That was the plan. That, of course, is not what happened.

The Endurance began to hit icebergs within days of leaving South Georgia. The ship proceeded to slalom through the ever-encroaching ice-pack for weeks. By mid-January 1915, they were completely trapped in the ice. By late February, the Endurance ceased to operate as a ship and instead became the crew’s winter quarters.

(Bonus fact: 69 dogs accompanied the Endurance when she went South. Sled dog racing became a source of entertainment while the ship was ice-bound. Winners were paid in chocolate and cigarettes. Ultimately, the dogs – as well as Mrs. Chippy, a cat who belonged to the ship’s carpenter – were shot both to conserve supplies and provide food for the trapped explorers.)

When the ice started to break up in late July, the slow and inexorable demise of the Endurance had begun. In late October, the pressure exerted by the ice began to crush the ship’s starboard side. The planking buckled, and the ship immediately began to leak. The crew was eventually forced to abandon ship. Men, dogs, gear, provisions, sledges, and lifeboats were all lowered onto the ice floe. Less than a month later, the Endurance slipped beneath the ice entirely and sank to the bottom of the Weddell Sea. So, too, sank Shackleton’s dream of a transcontinental crossing.

The crew was left 346 miles from Paulet Island, the closest hope of food or shelter.

Over the course of the next five months, Shackleton and his men played leap-frog with slowly disintegrating ice floes. By early April 1916, the men had been forced into the lifeboats and were now at the mercy of the winds, the fickle movement of the ice, and the Weddell Sea. They spent a week like this before managing to land on Elephant Island – a mountainous, inhospitable tract of land in the South Shetland Islands. This was the first time the crew had stepped foot on terra firma in 16 months.

Now comes the crazy part.

If there was any hope for survival, someone had to go for help. In late April, Shackleton and a crew of five launched one of the lifeboats and set sail for South Georgia. How far is South Georgia from Elephant Island, you ask? 800 miles. Yes, that’s right: 800 miles of icebergs, open ocean, and hurricane-force winds in a 22-foot lifeboat. What’s even crazier than the fact that Shackleton and his men attempted such a crossing is the fact that they succeeded. It took three months, four attempts, and the aid of no fewer than four separate governments, but Shackleton was finally able to return to Elephant Island to rescue the remainder of his crew.

(Bonus fact: When the boat crew landed on South Georgia in mid-May, the men still had to cross a mountain range in order to reach the whaling town of Stromness, where proverbial salvation lay.)

The most impressive part of the story? Every single member of the Weddell Sea Party came home alive. Sadly, the same cannot be said of the Ross Sea Party.

From the outset, the Ross Sea Party was hampered by miscommunications, financial shortcomings, and inexperience. Problems began as soon as the Aurora’s crew arrived in Australia to prepare for their leg of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Namely, they found a ship in need of complete overhaul and a budget that was only 50% of what they’d expected.

In spite of these early delays, the Aurora arrived in Antarctica by mid-January 1915, but fortune did not favor her crew overmuch. In relatively short order, the landing crew lost half their sled dogs, and then the Aurora herself in early May 1915 when her moorings were ripped free during a gale. Ten men were left stranded on the Ross Ice Shelf with little more than the clothes on their backs. The other 18 crewmembers were still aboard Aurora, which remained trapped in the ice until February 1916. (Once freed, the ship sailed for New Zealand, arriving in early April.)

In order to survive the winter, the landing crew were forced to work quickly and improvise widely. They set about gathering supplies from supply caches that had been abandoned by previous expeditions – including Scott’s Discovery and Shackleton’s own Nimrod.

(Bonus fact: The crew even created the “Hut Point Mixture” tobacco, which was a mixture of sawdust, tea, coffee, and dried herbs.)

They met with some success and indeed continued to lay-in supply depots in anticipation of the Transcontinental Party, which of course would never arrive. Ultimately, their resources were too few, the terrain was too unforgiving. Three men died. Pushed to the point of complete exhaustion and further depleted by the effects of scurvy, Reverend Arnold Spencer-Smith (chaplain and photographer) died in March 1916. Aeneas Mackintosh (Commander of the Aurora) and Victor Hayward (general assistant) were both lost during a blizzard in May 1916; they were supposed to have fallen through the ice, though their bodies were never recovered. In mid-January 1917, the remaining crew members were rescued by the Aurora, which returned to Antarctica after being repaired and refitted in New Zealand.

(Bonus fact: Recognition was slow in coming for members of the Ross Sea Party. They had succeeded in creating a supply route for the Transcontinental Party, but it was all for naught. Shackleton would eventually write that the men who died “gave their lives for their country as surely as those who gave up their lives in France or Flanders.”)

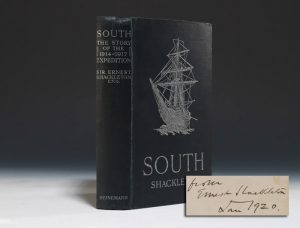

Upon returning to England in 1917, the men met with little fanfare and no time to recuperate. World War I was in full swing, and most crew members immediately took up active military service. Not surprisingly, Shackleton’s account of the Endurance expedition, South, didn’t appear until 1919.

Click here for Shackleton: Part III, the final episode in Shackleton’s Antarctic adventures.