What do we mean by the revolution? The war? That was no part of the revolution; it was only an effect and consequence of it. The revolution was in the minds of the people

, and this was effected from 1760 to 1775… before a drop of blood was shed at Lexington. The records of thirteen legislatures, the pamphlets, newspapers in all the colonies, ought to be consulted during that period, to ascertain the steps by which the public opinion was enlightened and informed.

– John Adams letter to Thomas Jefferson, 1815

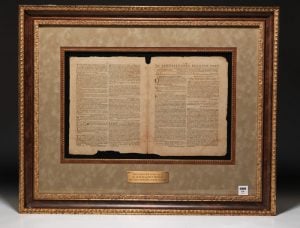

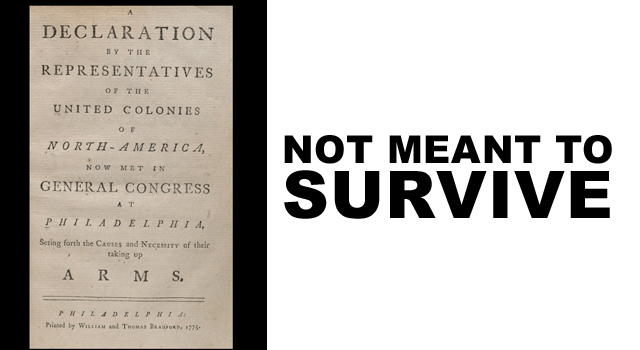

The United States of America was the first nation created though revolutionary acts of writing. Many of our most significant and influential founding works—Common Sense, the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Federalist Papers—were first printed not in book form, but as ephemera, printed material not meant to be preserved.

There are many types of ephemera, but in this series I’ll be discussing late 18th-century American pamphlets, broadsides, and newspapers. They were usually printed for a particular time-sensitive purpose and then discarded, so relatively little from this period has survived.

Ephemera captured history as it happened and quickly spread it on both sides of the Atlantic—breaking news, public reaction to current events, government declarations and documents, speeches, letters, sermons, essays, and furious debates about the political, economic, and philosophical issues of the day. These invaluable primary sources are like time travel, allowing us to witness key events, gain insight into everyday life, and understand how Americans evolved from loyalty to rebellion to self-government.

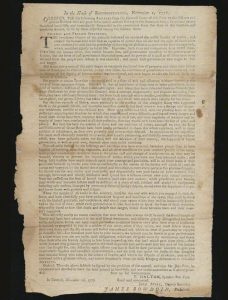

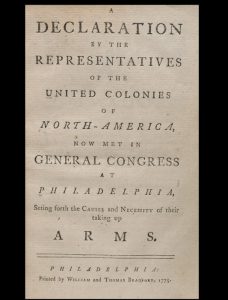

The more popular or important the work, the more likely it was to be reprinted in multiple formats and editions in different cities. State papers like the 1787 Constitution and the 1775 Declaration… Setting forth the Causes and Necessity of their taking up Arms were printed in newspapers and as broadsides and pamphlets.

With ephemera, as with books, the earlier the printing—the closer to the original event or publication—the more scarce and desirable it usually is. The earliest printings of some works are virtually unacquirable because so few copies exist or most known copies are in institutions.

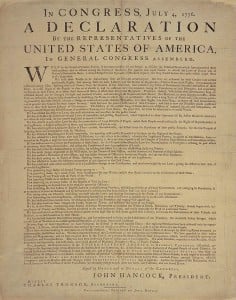

The most famous example is the Declaration of Independence, first printed as a broadside by John Dunlap and delivered to Congress the morning of July 5th, 1776. The first newspaper to print the Declaration was the July 6th Pennsylvania Evening Post, followed by the July 8th Pennsylvania Packet. As copies circulated and were mailed or carried to other cities, other printings of the Declaration quickly followed. There were 29 American newspaper printings in July and over a dozen broadside editions printed in July and August.

There are only 26 surviving copies of the Dunlap broadside, and all but two are in institutions. The other broadside printings are exceptionally rare (some have only one or two known copies), as are the first newspaper printings. Though these earliest printings of the Declaration may be not be acquirable, there were many other printings in various forms (in books, pamphlets, magazines, and broadsides) over the months and years that followed which are collectible.

This is also true of other ephemera from this period. If the earliest printings of important documents or publications are out of reach, there are likely other contemporary printings that are obtainable and still significant. Each piece has its own history—where, how, and why it was printed, who published, read, or owned it, and how many copies have survived to this day.

Collecting ephemera is an exciting way to rediscover and preserve the extraordinary history of America through the stories, struggles, achievements, ideas, and writings of Americans. Be sure to check back for new articles in my American Ephemera series as I explore the Revolution through pieces of print that were never meant to survive.

Comments

One Response to “American Ephemera: History as it Happened”

Matt says: August 25, 2013 at 1:16 am

Very informative and clear in explaining the rarety in your blog keep the good work up.